Catch Fish with

Mike Ladle

Information Page

SEA FISHING

For anyone unfamiliar with the site always check the FRESHWATER, SALTWATER and TACK-TICS pages. The Saltwater page now extends back as a record of over several years of (mostly) sea fishing and may be a useful guide as to when to fish. The Freshwater stuff is also up to date now. I keep adding to both. These pages are effectively my diary and the latest will usually be about fishing in the previous day or two. As you see I also add the odd piece from my friends and correspondents if I've not been doing much. The Tactics pages which are chiefly 'how I do it' plus a bit of science are also updated regularly and (I think) worth a read (the earlier ones are mostly tackle and 'how to do it' stuff).

Lure fishing in the 2020s - Part V

Pike

The pike's year

For once Harry and I were not fishing but were pike-watching, alongside a deep ditch that ran away from the main river. The channel cut across the meadow as straight as the proverbial ruler; it was an old ditch with reeds and sedges crowding its edges, here and there a young alder tree was rooted in the soil at the side, its branches hanging down towards the water. We moved slowly along the bank, trying to avoid being seen by any fish in the shallow water. Suddenly we both stopped dead; down below was what we had been hoping to see. There in the dim light were four, log-like shapes, one much larger than the others. A big female pike well on the way to thirty pounds had entered from the river and, with her three lesser consorts, had made her way to a thick clump of reeds where, in an orgy of thrashing fins and turbulent ‘rust-coloured’ flecks she shed almost 4lb of tiny translucent eggs, each one just under two-millimetres in diameter. The spawning over, the pike left as quickly and silently as they had entered.

In the cold April water, the little eggs, glued to the tough weed stems, would begin to develop. Many of the eggs would be infertile, becoming opaque and falling prey to the tiny aquatic fungi and bacteria which infest the ditch. Many more would be rasped and eaten by wandering snails, sucked by tiny spidery mites, or torn to pieces and swallowed by sticklebacks.

In due course, like pieces of knotted thread, the tiny pikelings would emerge from their eggs and cling tightly to reed and weed stems, feeding on microscopic algae, ciliates, rotifers, and water-fleas, all the time the numbers being reduced by continuous depredations of mantis-like water scorpions, shiny water-beetles with curved piercing fangs and the even stronger, crushing jaws of camouflaged caddis larvae.

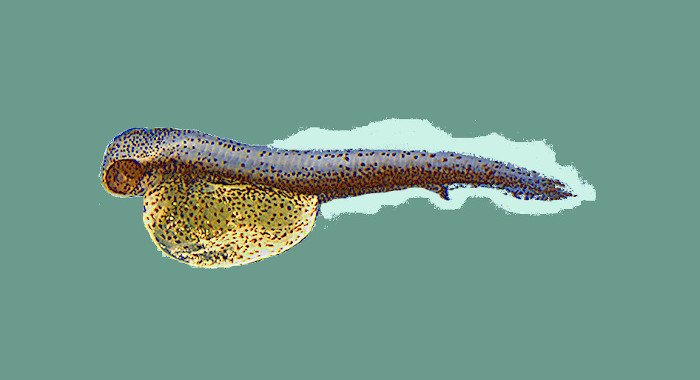

Newly hatched baby pike.

The water would be warming up quickly now, and the young pike growing rapidly. As they increased in size and became more like their parents in appearance, they would begin feeding on larvae and then fry of other fish which had hatched from eggs much later than themselves. In the River a few of the young pike would be eaten by trout and salmon parr, many more might fall prey to marauding perch, but the majority would be snapped up by the arrow-like lunges of their elder brothers and sisters. At one year old the survivors (now weighing over 4oz) would be feeding on the roach, dace, and minnows, which would be their food for the remainder of their lives.

looking a bit more pike-like.

Now it's a beautiful pike.

By the following year, the male pike would weigh roughly a pound, the females about twenty-five-percent more. Most of the pike, of both sexes, would now be mature, with the larger fish developing first, and by the age of eight the females could be twice the weight of the males. The above account is, more-or-less, typical of pike in some lakes or in a rich lowland River such as the Dorset Stour. In many other waters, growth is considerably slower. Where the average temperatures are generally low, the pike, like many other fish, grow more slowly but live longer and could ultimately reach a greater size than their counterparts which exist at higher temperatures.

These fish, taken from the same ditch at the same time, are of similar age. The larger one could easily eat the other one.

My first pike

It was in a lake in the North of England that I saw my first Pike. When I was a teenager my summer Holidays were usually spent fishing in the sea. Coalfish, codling, flounder, and plaice were the normal catches, but it was on one such holiday that I really discovered coarse fish. The discovery was made in a flooded, derelict, limestone quarry on the coast of Northumberland. On the South side of the quarry rugged, grey cliffs of hard, carboniferous limestone fell almost sheer to the water surface. There were only one or two access points to ledges near water level. Few plants gained a root-hold on the steep rock faces and the water was extremely deep and crystal clear. The opposite, North bank, 20 or 30m across the deep water, was a meadow of stony soil, thinly clothed in short grass, which sloped gently into the water’s edge. Along the shallower slopes of this North margin, dense thickets of feathery, red-stemmed, water milfoil were interspersed with clumps of the floating, wax-coated, oval leaves of pondweed.

During the first couple of summers at the quarry, my pal Bob Sprawling and I fished intensively; first for the small perch which were unbelievably abundant; then, as our skill increased, for roach which ranged in size from the usual twenty to twenty-five centimetres, up to a massive fish of two-and-a-half pounds caught, as dusk fell, on a margin-fished lump of bread. Eels were also present in this quarry and many of them were very-large. Almost every evening we were down at the ‘quarry pond’ legering for them with herring-strip or lobworm, and we landed some very big specimens. It was whilst fishing for eels that I caught my first pike. I was slowly winding in my lobworm bait when there was a sharp jerk on the end of the line, it proved to be a superb little fish of about a pound; not only the first pike I had caught but also the first one either of us had seen alive.

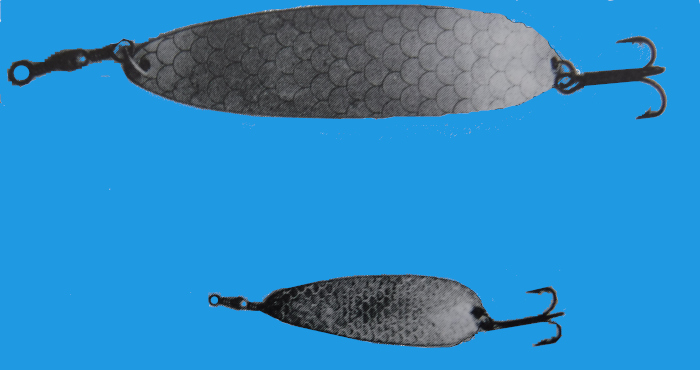

On the following day we took the bus into Alnwick, to visit the tackle shop and buy some ‘pike spinners’ and 10lb nylon. I sought the advice of the shop assistant but, in this game-fishing area, it turned out to be Hobson's choice. The only ‘spinners’ were simple, spoon-shaped, spoons. Chromium plated and armed with a single tail treble, they came in two sizes, 1.5 or 2 inches in length.

Lessons learned

In the following weeks, a few pike of up to six pounds in weight fell to the spoons. Our tackle was quite unsuitable for spinning but, by improvising, it was possible to fish many of the better spots. The rod that I used was a 12ft, tubular metal, tank aerial, purchased through the mail order columns of Angling Times (yes, there was mail order in the ‘olden days’). The reel was a small wooden centre-pin. Two basic methods were used. The first involved stripping off a few metres of line before swinging the spoon out between the weedbeds. For the second approach (to give a longer retrieve) the spoon was laid on a stone in the water’s edge and 30 or 40m of line were paid out as we walked away along the bank. The spoon was then jerked in and reeled back parallel to the bank. Both tactics were successful, and the excitement was intense because it was possible to see almost every ‘take’.

Gradually, patterns emerged from the simple spinning activities. Despite the minor size difference, the small spoon seemed to take many more perch than pike, while the reverse was true of the larger one. Other lures were tested, without much thought involved in the choice. Metal, Devon-minnows (sold for salmon fishing) were tried and found wanting in the still, clear water; the heavy lures needed to be retrieved much too fast to make them ‘work’ effectively and this resulted in a lot of line-twist. Cheap, plastic plugs (floating-divers) caught a few fish and often resulted in exciting surface strikes as they wriggled above the weedbeds.

Noting the apparent success of the larger spoons for pike, I invested several week’s pocket money in a ‘Jim Vincent Broads Spoon’, a heavy, 15cm, plate of (apparently) stainless steel. The idea was to try and tempt one of the bigger pike, for we had seen one or two ‘monsters’ following dead-baits (intended for eels) on the retrieve. My first attempts with the big spoon were not encouraging; it flapped and swung about in the water beautifully and it had plenty of weight to cast out, even on the crude tackle, but nothing showed any interest. Confidence soon ebbed and the ‘Jim Vincent’ was consigned to the tackle bag to be dug out, now and then, for a few casts; more in hope than in expectation.

My old 'Jim Vincent' - long gone - and a more normal sized spoon.

One day, at the end of August, I was working my way along the North bank casting across towards the steep cliffs and retrieving as deep and slow as I dared. Just as I reached the narrowest point, I was staring intently into the black depths for a first glimpse of the great twisting, flashing spoon. There it was! Gradually its form became clear as it ‘swam’ up the sloping shelf. Suddenly a huge green shape emerged from the darkness and swept, in a graceful curve, past the spoon, narrowly missing the stern treble. I was so startled that I whipped the lure from the water and held it dangling from the tip of the tank aerial as I attempted to control my trembling hand and pounding heart.

Would it come again? I guessed not, thinking that the pike must have seen me standing there. Foolishly, as it turned out, I swung the lure out three metres and began to draw it back simply by slowly raising the rod tip. A couple of seconds elapsed and suddenly there was the big fish again - but this time it clearly held the large spoon firmly clamped in its massive jaws. Little of the spoon was visible, but the swivel stuck out from the left side of the fish’s mouth and on the right the hook hung loosely. Again, panic set in and I struck wildly, the rod creaked and bent, the pike's jaws parted-and the spoon twanged back and clattered onto the bank.

Not surprisingly, despite ten minutes of further effort the fish did not reappear, but I had learned two valuable lessons. First, that the big spoon was capable of stimulating large pike to attack, and second (more importantly) never spin in half-hearted fashion. Certainly, if I had cast out and retrieved from the reel, the spoon would have had more forward momentum and the rod would have been in a more appropriate position to enable a firm strike. The chances of setting the rather crude hooks would also have been improved.

Following these first attempts at pike spinning there was a long interval in which much time was devoted to reading about pike; it was clear to me that these were ‘my sort of fish’, even the small ones were a fair size. At least one approach to their capture involved an active, energetic, searching tactic, quite different from many of the sit-and-wait or chuck-and-chance-it methods with which I was already familiar. Also, pike-spinning represented a real challenge and there was obviously plenty of room for improvement in both lures and technique. So far, the small spoons, spinners and plugs had produced only smallish pike and, although the Jim Vincent had stirred a couple of much better specimens, clearly it was going to be a lot less productive than the smaller lures.

One of the larger spoons that I use these days. Lighter and easier to fish with than the Jim Vincent.

Harry had also been accustomed to pike fishing in ponds and lakes, usually catching small fish on spoons of various sorts; his biggest being only about six-pounds, although he too had lost a ‘monster’ pike, in Carr-Mill dam (near Saint Helens, now filled in), which had taken both the spoon and his end tackle. Sadly, on my last visit to the beautiful quarries where, I cut-my-teeth on pike spinning I also found them filled in and thick with rubbish.

Harry and I both moved to Dorset in the early 1960s and, when it came to fishing for pike in rivers, we obviously had to have a rethink. Because of our separate beginnings, and even though we both fished with similar tackle, we tended to approach our fishing in different ways. Later, we would compare notes, discuss results, and try to find out why one method was more successful than another.

A Rethink on pike

Even a cursory inspection of the angling magazines showed that most large pike were caught by anglers using live or dead-fish baits. Was this because of the nature of the baits or was it simply that natural baits were usually larger (and moved more slowly) than most artificials? Could it also be because spinners, spoons, and plugs were probably used less often than natural baits? After all most anglers seem much happier when they are sitting on a box watching a float or bite indicator than using more active methods. There were several writers who were enthusiastic lure fishers. Thurlow Craig, in his books Spinners Delight and Bait Makers Delight, described a vast range of lures, some of them obviously practicable and others which had so many joints and hooks that the mere thought of trying to cast them is enough to send a shudder down the spine.

Richard Walker, who was a shrewd judge of methods and an advocate of big baits for big fish; he described in his excellent book Still Water Angling his own failure to catch large pike and his (unusual) lack of success with the species, while at the same time depicting a ‘wounded rudd’ plug and suggesting the possibility of making a replica of a moorhen to attract the big ones.

More recently, like Thurlow Craig before them, Barry Rickards and Ken Whitehead, both mad keen on spinning and plug fishing, gave long lists of spinning lures without solving (at least, to our satisfaction) the problems of matching the ‘natural’ for numbers and sizes of pike caught. Perhaps there is no complete answer to the pike-lure selectivity puzzle, but it is certainly possible to improve results.

To me the most likely approach was to get some reliable information on the behaviour of pike and on their eating habits. The pike is a lurking predator; an ambushing, stalking, highly-efficient, whiplash of a fish. In some ways, as we have already said, such fish are less easy to catch than freely-swimming hunters. Because of their lurking tactics, pike tend to have plenty of time to consider their course of action when they encounter prey. Any spinner, spoon or plug which fails to represent the characteristics of a food-fish is likely to be rejected out of hand (or should it be out of mouth?).

Food facts

There have been many scientific studies dealing with what pike eat in different waters. It goes without saying that the predators can only feed on fish which are present. So, in a Northern lough or loch, the only available prey may be countless stunted perch and the young of the pike themselves. In a large Lake District lake, enriched by silt, fed by streams draining agricultural land and augmented by sewage effluents, perch may be the main food items, but roach, charr and trout will supplement the diet. In lowland meres and broads, rudd tench and bream are likely to be the staple foods. In the stony, rivers of the North West the main prey will be trout and minnows; while grayling, dace, roach, chub, barbel, seatrout, salmon, bullheads, gudgeon or minnows are eaten in larger lowland rivers. The angler must consider matching the shape, form, and movement of his lure to the species for which the pike will be searching. The object should be to make sure that the pike recognises the lure as food (it must look right), but also to evoke the feeding response by presenting it as a fish isolated from its fellows, showing characteristics of confusion, within easy reach, and slower moving than normal.

It is a well-known scientific fact that, on average, the largest pike eat the biggest prey. A fish of little more than one metre in length could manage a chub of almost half its own length - a fine specimen. Even the largest pike, however, often eat large numbers of prey only a few centimetres in length. In waters where minnows are abundant, they are usually the most frequent food items of the resident pike of all sizes. This pattern would be more or less typical of pike in large, hard water lakes, or even in a rich, lowland River such as the Dorset Stour.

A fat minnow - often abundant items on the pike's menu.

Are the pike selective or are they not? There have been various studies which throw some light on the matter, but first, just take an example from a river which Harry and I fished for both pike and salmon. Throughout the salmon season every inch of water was combed, almost daily, by anglers using a wide range of smallish, (mostly less than 3”) artificial lures. Quite often the reward for a hard session of salmon spinning in the frosty conditions of early spring, is a sharp ‘snatch’ and a brief encounter with two or three pounds of green, glistening, toothy, out-of-season, disappointment. Most of the pike caught by salmon anglers are small fish in the first two or three years of their lives. Why?

Small pike can be a nuisance and they still demand a wire trace.

Just to emphasise the point, in the early 1970s, outside the salmon season (March to October, in ‘our’ area, in those days), my pals and I spent several years fishing a small, local river for pike, using artificial lures only. At first, we tried ‘salmon lures’ Mepps, Tobys and small plugs of various types, and the average size of the pike caught was a couple of pounds. Apart from one rare exception (a twenty-six pound fish taken by our pal Jon on a 3” plastic plug) the biggest specimens landed were only about 8lb in weight and even these were quite scarce.

In fact, it turned out that big pike were numerous in the water fished, because when, years later, we switched to the use of live or dead fish as baits (and much larger lures), one in four of the pike which we landed was in double figures, with plenty of 20lb plus specimens. For the moment we will assume that the smaller fish were naive or stupid and the larger ones somehow ‘educated’. There were probably several reasons for this apparent ‘lure selectivity’.

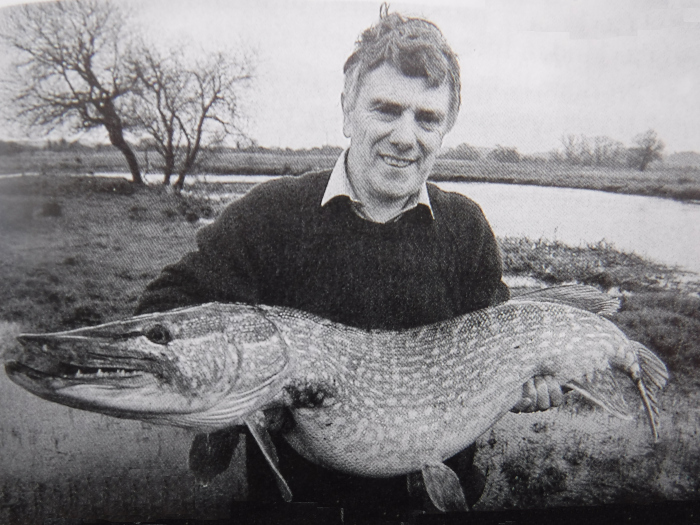

A cracking pike caught on a bait from the river just behind me (and a much younger me).

Educated pike

The ‘catchability’ of pike was examined by doctor Beukema, a Dutch scientist, who compared the effect of using spinners with that of small live-fish baits. All the pike caught were immediately returned to the little experimental pond and very few died as a result of being landed. Prior to the experiment, the pike used had never been angled for, so they were not ‘educated’. Every one of the 79 fish in the pond was tagged so it could be recognised, and the results of the experiment were very revealing.

After about half of the fish had been caught on spinners (Mepps-type spinners) they became very difficult to catch by using this method. In contrast, their ‘catchability’ on live-baits was not affected by being caught, either on spinners or on live fish. Significantly, it proved extremely difficult to catch any of the pike more than once by spinning, but the fish never seemed to learn about live-baits and could be caught again and again.

Despite the apparent fact that pike quickly learn to avoid taking artificials, they are (thankfully!) not infallible. In fact, they are suckers compared to some other species of fish. Anyone who looks at the angling magazines will have realised that individual large pike are often caught more than once, particularly by anglers using live- or dead-fish-baits. We, ourselves fished in a river in which many of the pike were labelled with numbered jaw tags and found it possible to catch the same fish repeatedly. It can be very impressive to predict to a visiting angler, not only where a fish will take the bait or lure but (as I did on one occasion), to say that “it will weigh 17.25 lb”!

Don't bite off more than you can chew!

However, sometimes the catch is not quite what you expect, as Harry found out. It was mid-summer, and the river was low and clear. To pass away his lunch break he was hopefully spinning with the small Mepps-Mino on 6lb nylon, with a view to tempting a seatrout; while I sat on the bank and criticised his efforts. Suddenly there was a swirl, a flash of metallic green and a tug on the line, as a pike of about 2lb darted onto the passing lure. I watched and chuckled as the little fish kicked and struggled, commenting that “they don't come much smaller than that!” as the words left my lips, a fish in the 30lb class lunged from its resting place in a bed of pondweed and seized the smaller pike square across its great jaws.

We peered into the depths, where we could catch the glint of the Mepps’ blade, still wedged in the scissors of the small fish. As our eyes became accustomed to the light, we could see that the head and tail of the ‘jack’ were just showing on either side of its captor’s head. Harry quickly flicked off the bale arm of his reel and allowed the line to run freely, as the big predator turned away. The pike moved off a couple of metres and settled down, more-or-less in its original lair.

Harry opted for a quick strike, fearing that the big fish would nick the fine line with its teeth. He hit the pike as hard as he dared, bending the rod into a deep curve. The massive green shape lifted slowly and moved sedately in the direction of the pull. When it was about 5m from the bank the great jaws yawned wide, releasing their victim. The big pike turned tail and slowly cruised away – the small hooks had never even touched its mouth. The problem was of course that, in the absence of a wire trace, Harry had been reluctant to let the monster turn its prey. Although, in this case, the attraction was natural (a real pike) rather than artificial (the lure); this, wire-trace, problem lies at the heart of all freshwater spinning where pike are present.

The large size of a pike’s mouth, and the uncompromising nature of its attack, makes it liable to engulf any small lure. Once inside that roomy interior it becomes a matter only of time until the line contacts the fish’s personal set of needle-like, nylon cutters. Here lies the only real difference between spinning for pike and for other freshwater species in the UK. If you are to avoid frequent lure losses it will be necessary to

1. Link the lure to the main-line with a length of wire, or

2. Use a lure big enough to stand a fair chance of separating the line from the pike’s teeth.

The former is always preferable, as even large lures may be taken by the front end. These days it is possible to obtain excellent, knottable, trace-wire, so a trace is essential when fishing in any water containing even the smallest pike. No experienced pike-angler is likely to be unaware of the danger of ‘bite-offs’. A couple of examples will serve to illustrate the point.

Always use a wire trace.

While I was fishing, for salmon, with a small Canadian Wiggler (a metal ‘flat-fish’ lure) in the clear waters of the Dorset Frome, a large pike, shot out from the bank beneath my feet. The lure disappeared into its mouth and, without the slightest snatch, tug, or pluck, it left me with the 12lb nylon fluttering from the rod tip.

On the second occasion I was spinning with my large, ‘Jim Vincent’ spoon, tied direct to 18lb line. A tiny jack pike of less than 2lb, attacked the lure, missed it completely, and sheared through the line just above the lure, which sank to the riverbed in two metres of water. When the spoon was subsequently retrieved (after much prodding about with the rod top) the knot was intact and the line was cut, as though by scissors. When fishing unknown water, even if the presence of pike is in doubt, it is always wise to use a wire trace. In my experience, the use of wire is unlikely to ‘put off’ any other worthwhile fish.

Knottable wire won't deter chub or perch from taking your lure.

Pike, American style

Further information is available from North American anglers, who have several species of Pike in their waters. The two of most interest are, the northern pike (our own Esox lucius), and the larger and even more desirable muskellunge (Esox masquinongy). Two scientists, Weitman and Anderson, stocked eight small ponds with these fish to see whether one species was easier to catch than the other. Two of the ponds had only (Northern) pike two had only muskie's, two had tiger-muskies (a cross between the two species) and the last two ponds held equal numbers of a mixture of all three types.

In fifty-eight-hours of spinning with Mepps spinners, spread evenly between ponds, fifty-nine of the fish were caught. Despite the presence of equal numbers, two-thirds of those caught were (Northern) pike and the rest were about equal numbers of muskie and tiger-muskie.

Of the twenty (Northern) pike in the ponds, each one was caught at least once, and one was caught no less than 7 times! The scientists said that the pike (even though the Dutch experiments showed that they quickly learn to avoid spinners) were about four times easier to catch on Mepps than were the muskies and three times easier than the tiger-muskie hybrids. Fish were handled many times but very few died due to hooking and even three deeply-hooked fish recovered and survived.

The pike has millions of years of natural selection behind its ability to distinguish the edible from the inedible. Each year's crop of young, inexperienced pike contains a share of the slow, the short-sighted, the unlucky and the down-right gormless. These unfortunates fall prey at first to fierce predatory insects, then to larger fish, to birds and ultimately to pike anglers (hopefully in this case they are returned alive). Once the simpletons and the unlucky ones have been weeded out or ‘educated’ to the dangers, which lie in depending only on simple flash or vibration to signal food, they become much more difficult to tempt. Anything about a lure which does not look fully acceptable as a meal may cause it to be inspected and then rejected. Spinning for pike, depending upon the circumstances and whether the fish are already ‘educated’ or not, can be extremely rewarding or very discouraging.

The last word on pike

In a book about lure fishing, it may seem inappropriate to write about other ways of catching pike. However, it would be foolish to avoid the truth. These days fly fishing for pike with very big ‘flies’ resembling budgies (in both size and colour) has become popular, particularly on some large lakes and reservoirs. This, fly fishing, is a ‘fashion’ and has caught numbers of big fish, particularly from waters stocked for trout fishing, where there are lots of large, trout-fed pike to be caught.

Nevertheless, fly fishing ‘works’ but it is a simply a different way of presenting, slowly and erratically, a large ‘imitation fish’ to the pike. It differs only from using spun lures in the fact that specialised rods, reels, and lines are required, and both the tackle and the methods of using it need to be learned. In fact, there are now plenty of spinning lures which achieve exactly the same result. Notably, large, shallow-diving plugs and unweighted, soft plastics with waggy or wriggly tails.

The large, soft-plastic lures have all the attributes of a ‘pike fly’ and can be fished using spinning tackle, which will cast them with a good deal less fuss and disturbance (so possibly more effectively) than is required with fly gear. In short, the only real reason for using fly tackle may be because you enjoy the casting process and/or because you prefer playing fish on a ‘centre pin’ type reel - nothing wrong with that of course and it may be the only permitted method – but certainly not because it is likely to catch more or larger pike than other tactics. The success of the approach may suggest that it is worth using a large lure which is unfamiliar to the pike (one that they have not yet learned to avoid). If you really want to catch more large pike, there is a hierarchy of methods which I believe are most likely to succeed, as follows: -

1. Live-bait on float or bottom tackle – I prefer to use a single circle hook through the top lip of the bait.

Circle hooks usually find a hold round the maxilla.

2. Dead baits fished either static or (I think preferably) by slow wobbling. Again, on a single circle hook through both lips of the bait.

3. Spinning slowly with large, unweighted soft plastic baits on single, crank-shanked hooks or (if you want to) fly-fishing with big flies.

My pal Stuart with a nice fly-caught pike.

I think that these weedless softbaits are good alternatives to flies for pike.

4. Spinning with a wide variety of large lures, including plugs, spoons and spinners, multi-hooked and other.

5. Spinning with small lures.

Pike will take a great variety of lures - large and small.

Of course, some anglers have ethical objections to a method, others prefer a more active approach to their fishing rather than a sit-and-wait tactic, lure fishing may help to ‘search more water’ than the static approaches and for sure there may be specific circumstances – deep water, snags, non-availability of baits, and so on, which favour one or other of the above tactics but, if you simply want to catch decent pike then these are the ways to go and remember, within limits, larger baits will tempt larger fish.

– PLEASE TELL YOUR TWITTER, FACEBOOK, EMAIL FRIENDS ABOUT THESE BOOKS.

ANGLING ON THE EDGE

Copies can now be ordered (printed on demand) from Steve Pitts at £34.00, inc. Royal Mail Insured UK Mainland Postage.

To order a book send an E-MAIL to - stevejpitts@gmail.com

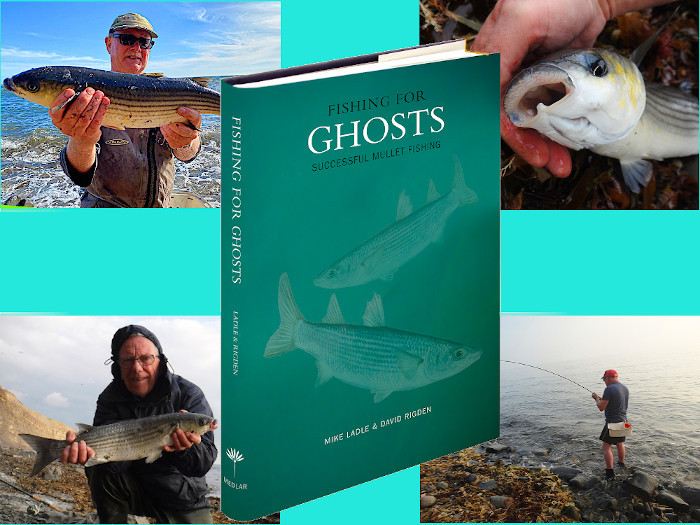

FISHING FOR GHOSTS

Written with David Rigden. Copies from

THE SECOND WAVE

Written with Steve Pitts this is a SEQUEL TO THE BESTSELLER "Operation Sea Angler" IT'S AVAILABLE ON PAPER FROM -

If you have any comments or questions about fish, methods, tactics or 'what have you!' get in touch with me by sending an E-MAIL to - docladle@hotmail.com