Catch Fish with

Mike Ladle

Information Page

SEA FISHING

For anyone unfamiliar with the site always check the FRESHWATER, SALTWATER and TACK-TICS pages. The Saltwater page now extends back as a record of over several years of (mostly) sea fishing and may be a useful guide as to when to fish. The Freshwater stuff is also up to date now. I keep adding to both. These pages are effectively my diary and the latest will usually be about fishing in the previous day or two. As you see I also add the odd piece from my friends and correspondents if I've not been doing much. The Tactics pages which are chiefly 'how I do it' plus a bit of science are also updated regularly and (I think) worth a read (the earlier ones are mostly tackle and 'how to do it' stuff).

Lure fishing in the 2020s - Part VI

SEA FISH

The fussy pollack

When this was first written, spinning for sea fish was a neglected branch of angling, but for any species which takes moving prey or feeds in the company of others of its kind, a lure of the right size, shape, colour and action can produce hectic sport. So, once again, what is the right lure? It changes not only from pollack to cod or from bass to mackerel but also with the time of year, with the age and size of the fish and with the fishing conditions. (if fishing were easy, and success assured, few of us would remain hooked on angling!)

A detailed example of such a change in diet with the age of the fish has been described by Drs Potts and Wootton of the Marine Biological Association at Plymouth. This information deals only with pollack and I shall use it to show how the best time, place, and method for catching a species may alter completely as the fish increase in size. A similar sequence of changes no doubt applies to most other predatory sea fish.

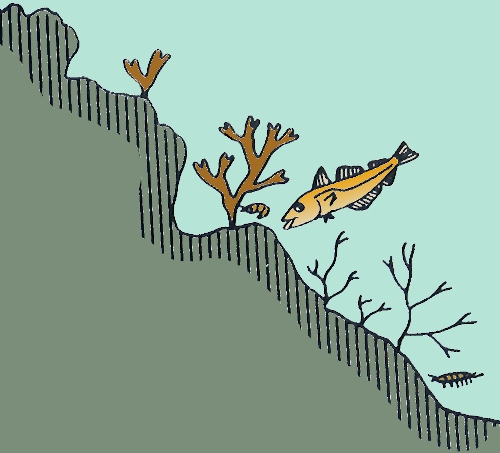

Baby pollack, when they first appear inshore, usually live in very shallow water or in estuaries, and feed mainly on tiny crustaceans which they pick from seaweeds or catch in open water.

Baby pollack seek small crustaceans among the weed beds.

When the fish reached about fifteen cm long (just the size when they can become a nuisance to anglers after bigger game, and when they can first be caught on a tiny, jigged lure or fly), they switched from eating crustacea to feeding on two-spot-gobies. The gobies are, at most, 7cm in length and unlike others of their kind, they swim near the surface of the sea around beds of wrack, kelp, or eelgrass. Often the little gobies shoal-up tightly over small clearings in the weedbeds and to catch them the pollack must change their hunting tactics to a pursuit method. This is highly successful because the young pollack are much faster and more powerful swimmers than the gobies.

Two-spot gobies are next to suffer the depredations of the pollack.

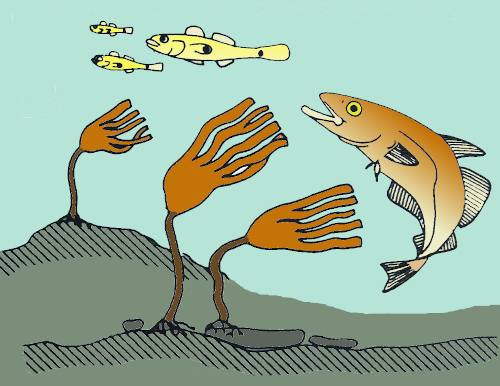

Soon the pollack, which are growing quickly, need a more plentiful supply of food, and to obtain it they switch their diet again, this time to baby lesser-sandeels which, in the hours of daylight, swim and feed in huge numbers over inshore, sandy bottoms. Unfortunately for the young pollack the sandeels are much faster and more alert than the two-spot-gobies and the pursuit tactic no longer works. The pollack are not slow to learn and they resort to stalking the sandeels from the cover of rocky outcrops. Any patch of rock, however small, located on a sandy seabed, will form a territory for pollack, and such cover is so desirable that the fish will actually defend their territory from other pollack which might compete with them for food.

Now worth fishing for, the pollack hunt sandeels around rocky areas.

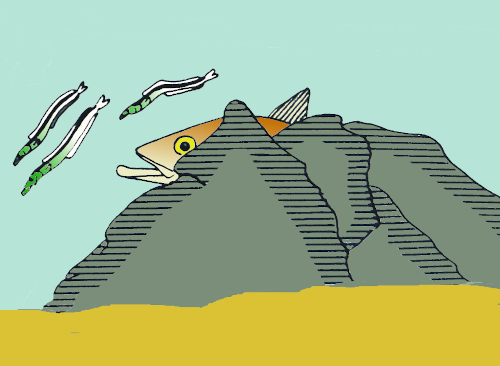

Over the summer the young pollack grow until they are thirty cm or more in length; quite big enough to provide interesting sport on light tackle. By now the tiny sandeels are no longer adequate food so the solitary, stalking tactic is changed and the fish gather into feeding schools, swimming in mid-water. These hunting ‘packs’ chase after various species of mid-water forage fish, particularly the large greater-sandeels, the pollack are much more versatile now and will also raid the inshore reefs for small ‘rock-fish’; pouting, poor-cod and other prey species, all are taken with characteristic lunging ferocity.

Larger, stronger, pollack feed on any fish they can catch.

It is at this stage that the larger specimens move out into deeper water to shoal over rocky pinnacles and wrecks. In the autumn and early winter, when rough seas pound the coast, these big fish will sometimes visit inshore grounds and, from our local Dorset beaches such as Chesil and Durdle Door, most years see the capture of a few fish well into double figures at this time. In late winter, the big fish gather on offshore marks to spawn, often in company with large coalfish, and it is then that the Redgill, Eddystone or live sandeel on a flowing trace, is likely to produce that fish of a lifetime for those with the enthusiasm, cash, and stomach to go afloat.

Pollack time

By scientific examination of the gut contents of captured pollack (or for that matter, of any other fish) it is possible to get some idea of when the fish are most likely to feed. Fresh, new, prey appeared in pollack guts most often in the early morning round-about first light. Later in the day the stomachs generally contained well digested prey. The fish will also feed actively at dusk, which is the time when we have caught large numbers by spinning with rubber eels or by fly fishing.

The sun is up and we're on the way home for breakfast.

In relation to shore fishing for pollack, I well remember my first experiences of catching these fish on lures. I was on a late-summer holiday in the Isle of man, and my favourite fishing spot was the rugged peninsula of Langness point in the South of the island. Wrasse and pollack were abundant in the deep, weedy gullies and, with my pal Bob I would spend the entire day float-fishing or paternostering for these fish with rag, lug, or crab baits.

On the morning of the day in question, the wind had shifted overnight and when we reached our favourite gully a gale of rough, cold air from the South-West was buffeting the rods as we tackled up. Six hours and a couple of small wrasse later we had almost given up hope of any reasonable catch. Cold and miserable, we decided to opt for shelter in the last hour of daylight. Picking up the gear, we crossed the short sea turf to the east side of the peninsula. As we scrambled down to the water level, the protection of the high rocky walls began to have its effect, and the calm surface of the water within the deep gully was a complete contrast to our previous pitch. Ten metres out the flat surface was suddenly broken as, with a plop, a twenty-five cm pollack flung itself into the air. Instantly our attitude changed, and we dug about in the tackle bag for something to attract the fish. Thinking that the pollack which had shown itself was likely to be typical of the others present, we tied small Toby spoons to our 10lb mono lines.

Metal lures can work well for fry feeding pollack.

Even in those days (the 1950s) our standard spinning rods were Mark IV carp rods, home- made from split cane, cut and glued in the workshop (kitchen) a la Richard Walker. Built for coping with 20lb plus carp, the rods were powerful ‘weapons’, and Bob and I were confident of dealing with pollack of any size in the 8m of water. On the first cast we realised that our confidence was misplaced. Bob's Toby was grabbed almost as it hit the water and the fish ‘sounded’ for the sanctuary of the kelp. A string of expletives greeted the dive as his rod crashed round into its fighting curve and the clutch screamed and released line. The steady pressure began to tell and shortly a 3.5lb, olive-gold, wet-look, pollack was flapping at the surface. As it was unhooked and returned, I struck into my own crash-diver and time and again our rods plunged towards the water as fish after fish, ranging from 1lb to over 6lb, mistook the little, flickering spoons for small fry.

In fact, despite the powerful tackle, we lost several large fish which made unstoppable dives for the refuge of the kelp stems. This habit of the pollack, of making a smart vertical dive is, of course, well known to wreck anglers. Even large pollack can be landed from quite shallow water when wrack, rather than kelp, is the main form of weed.

Plug fishing can be an expensive way of extracting pollack from the kelp beds.

The possibility of big pollack from shallow water was again brought home to me on Langness point, when I encountered one of the local lighthouse keepers carrying a stout bamboo pole (like a carpet stiffener); the pole terminated in a length of fixed line. As we walked together down to the water, we struck up a conversation about his gear. The heavy nylon tied to the end of the pole was armed with a hefty weight and three, good-sized, white-feathered lures.

The man proceeded to work the lures sink and draw, in the three or four metres of water covering a meadow of wrack on the sea-bed. The tide was flooding quickly into the gully and, as I watched, a bronze torpedo flashed from the wrack thicket and impaled itself on one of the feathered hooks. In short order a double-figure pollack was heaved onto the rocks and dispatched. Two other fish, only a little smaller than the first, followed quickly and it was clear from the angler’s manner and his comments that he had done it all before. I never managed to catch such a large pollack from the shallows, despite the lighthouse keeper’s tuition, but on a few occasions the sport with fish up to 5lb plus was spectacular. Before the accidental meeting I had never dreamed of catching such large fish from water scarcely deep enough to cover their backs. Many times, since then I have realised what I had been missing.

In the Purbeck area of Dorset, where I live, most shore-caught pollack are small. A fish of over 2lb is quite a prize. These little pollack provide excellent sport for lure anglers or, better still, on fly tackle. Fishing from the rocks at dusk (or preferably first-light) with a fly rod, a floating line and a small, Redgill or Delta type plastic-eel, sport can be hectic. The fish may tend to come in bursts of activity interspersed with short lulls. If your catches must be lifted onto the rocks, be sure to use a sufficiently strong (? 6lb) nylon trace or take a long-handled net with you.

A fly rod and a tiny Delta 'eel' give good sport with smaller pollack at dawn.

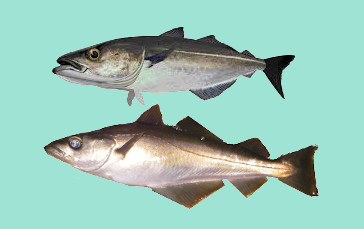

Coalfish, the pollack of the north

Pollack of various sizes provide sport for experienced anglers and practice for the less experienced around the South and West Coasts of Britain but, in the North and East, coalfish play the same part. Young coalfish (up to three years of age) will, like the pollack, take feathers and spinning lures. I recall feathering from the stone pier at Craster, Northumberland, and catching one coalfish after another. The biggest were 3-4lb in weight, but most of them were younger fish of about 1.5lb.

The straight, white, lateral line distinguishes coalfish from their relative, the pollack..

A small pirk or willow leaf spoon is also remarkably effective for these fish. Coalfish are generally regarded as a second-class fish in the North-East, with cod and codling being the prime catches. In years past, both spinning and fly fishing for coalfish were quite popular off the rugged scars at Filey Brig; near-surface-feeding ‘coalies’ were often caught by these methods in August and September every year.

Coalfish are generally very obliging. Even younger specimens eat lots of fish and will readily take lures. I have caught literally thousands of two- and three-year-old specimens from the quays and rock edges of Northumberland and Berwickshire. In suitably calm, warm, evening conditions, it may be possible to take; ‘a-fish-a-cast’ on light spinning tackle. In those days I was not aware of the benefits which can accrue from early-morning fishing trips. Larger coalfish are often caught on lures intended for mackerel. I recall vividly when I was a youngster, I went fishing with John Harper, a friend of my father, out of Castletown, Isle of Man. The basic idea was to troll a conventional mackerel-spinner on the way out to the ‘cod-marks’ and then to jig with a ‘murderer’ for cod, over the banks themselves. Both tactics sometimes produced large pollack and coalfish.

One of my strongest memories, is of the excitement in the boat when the heavy, hemp mackerel line in my hand yanked tight, and a strenuous tug-of-war resulted in the gaffing of a 12lb coalfish which, at the time, was the biggest fish I had ever caught. It took a mackerel spinner garnished with a silver-foil, sweet-wrapper. This started me on a fashion which took years to break. Modern sandeel imitations, spoons and plugs can be even more effective attractors of large coalfish and pollack and the use of Redgill or Eddystone style eels on flying-collar rigs, over wrecks and reefs at spawning time is now well-known tactic.

We have lift off!

Both pollack and coalfish tend to strike at lures from below and, in doing so, pollack may literally rocket from the water as they overshoot the bait. There are many examples of this sort of behaviour in the angling literature. Holcombe, in 1921, wrote - “a number of big pollack suddenly made their appearance in the wake of the boat, tumbling over and over one another, for all the world like a school of porpoises, and one fish, of some 9 or 10lb, was actually gaffed into the boat close to the rudder.”

Another classic example was described to me in 1984 in a letter from Mike Browning of Milford Haven, Wales. Mike spent a lot of time trolling with Redgill lures for bass, but he was keen to try other lures which might improve results. He wrote as follows, and I give the full account to show the possible scope of lure fishing: -

“I fished all day with a large sinking Rapala (mackerel type). Not a fish looked at it. At the end of the day- with dusk falling - I decided to head for home. I opened-up the engine and, in a filthy temper, reeled in the plug as fast as possible. As it came to the surface, I saw a large mouth behind it which enveloped the lure within a foot of the surface. The fish (a porbeagle I think) then turned, causing a torrent of water to pour over me! I returned to the Harbour wet and very thoughtful, and poorer by the £5 cost of a Rapala.” (the price shows that it was some years ago).

“On the second occasion we were trolling with Redgills and plugs, but the ‘driver’ placed his rod down so that he could concentrate on steering in a dangerous area. His lure, a large Rapala, was bobbing about in the wake of the boat about one metre back from the propeller. Three of us in the stern saw a large pollack appear from the depths and try to seize the lure - it missed but the force of its pursuit carried it a metre or more above the surface. It was at least 10lb.”

Presumably, the fish are attracted to the bubbles and cavitation effects in the wake of boats. The many silvery reflections may well resemble shoals of small baitfish, suggesting that a hose, played onto the water surface in late evening, might drive pollack and coalfish into a feeding frenzy.

The cod, a sociable feeder

To start this section, I’ll include an extract from one of my early web pages; this says a good deal about the behaviour of cod.

Eat or be eaten! Whether on land or in the sea this is a fact of nature. We have all watched TV pictures of hunting predators on the plains of Africa, the lion, the cheetah or the hyena singling out the young or weak specimen of its prey before catching and eating it. Things are no different for the fish around our shores. There is a constant struggle between hunters and hunted, large and small, weak and strong. Most of the fish that we like to catch are designed to prey on smaller animals and many of them eat other fish. Of course, in its young stages even a fierce predatory species like the cod has to ‘watch its back’ or risk being devoured by something bigger, even including its own uncles, aunts or grandparents.

A couple of studies show just how tricky it is to be a cod. Fishery scientists like to research what they call ‘habitat’ - which simply means the sort of places that fish like to live in. It is well known that young/small fish often live in or around cover (hiding places) to give them a chance of dodging predators. To test this idea some Canadian researchers studied how young cod managed to avoid their older brother and sisters. The experiment was carried out in tanks and the baby cod were given the choice of sand, gravel, big stones or a clump of kelp to hide in. Bigger, three-year-old, cod were introduced to the tanks as predators.

If there was no big cod in the tank or if the big cod was in there but had decided to take a rest (no they aren't always on the feed) then the little cod preferred to swim about over the sandy sea-bed and avoided the kelp (at the same time keeping well clear of the predator). If, however, the big cod decided it was hungry and began to forage about the tank, everything changed and the little cod, sensing the danger, dived for cover. Surprisingly, given the choice, the baby fish hid among the big stones and the kelp was only regarded as a second-best refuge. When they were able to tuck themselves away in either stones or weed there was much less chance of being eaten.

Presumably hiding among and under stones gives these baby fish better protection than lurking among waving weeds and little cod are not the only ones to realise this. I have often seen young mullet and bass, which normally swim around in shoals, disappear like magic when they were disturbed. By searching about with my hands and turning over stones the refugees were often discovered neatly tucked away in crevices.

Many years ago, there was a television programme in which several species of tropical fish were shown turning over large rocks to get at the animals hiding beneath while other opportunist fish looked on. It would surprise me if some of our own predators, perhaps large cod or wrasse, do not use exactly the same tactics. In fact, cod are well known stone turners.

From a quite different point of view another Canadian study was interested in just how much big cod move about when they are in the sea and also how they shoal together. In this case sensitive echo sounders were used to follow the yearly shoreward migration of cod shoals, over the Newfoundland shelf, which occurs every spring. It was found that both the tightness of the shoals and the rate at which the cod swam were closely associated with the presence of pink shrimps in the water. Pink shrimps are those big pink ‘prawns’ which you can buy at any fishmongers. These juicy crustaceans, even when dead and cooked, are a superb salmon bait and when they are alive and kicking, they are an important food for cod and other fish.

A cooked, fishmonger's 'pink shrimp', live ones are cod caviare.

The shrimp shoals show up on echo sounding traces as background ‘scatter’ so it was possible to tell where their numbers were thickest. The migrating cod which were usually swimming towards the coast at a speed of about 20 km per day dropped their speed to only about 5 km per day when they encountered large numbers of shrimp. Presumably, the wealth of food was just too much for them to resist and the fish got 'stuck in' when they had the opportunity. Even the urge to migrate was overcome by the chance of a square meal.

A second interesting observation was that the feeding cod shoals spread out from the sea-bed to match exactly the depth range of the shrimp hordes. This upward and outward spread meant that the cod were swimming in open water anything up to 85 metres off the bottom. The cod would not rise any further from the bottom than this even if there were lots of shrimps at shallower depths. When the cod were feeding on these big concentrations of shrimps the shoals actually dispersed to do so and at times the individual fish were as much as eight body lengths apart. This means that in a shoal of big fish (say 1 metre long) the feeding individuals could be up to eight metres from one another. The scientists interpret these changes in swimming speed and shoal structure as ways of making the most of the rich food supply.

Why do cod shoal in this way? Well, for any fish, being in a shoal probably gives them a number of advantages when it comes to avoiding predators. Of course, you might think that a fish swimming 'in a crowd' would have more competition for food (less shrimps to go round) but at the same time it can feed more freely because there are more pairs of eyes on the look-out for danger. All in all, these snippets of information are simply a couple more pieces in the great puzzle of what makes our favourite fried fish supper the great success which it is.

Cod are themselves equally as predatory as their sleeker cousins, the pollack and the coalfish and, as mentioned, they often swim in schools. In the case of small fish this is a method of protection from predators, but the bigger fish will gather for feeding. These feeding groups are believed to be rather loose and widely scattered, with the fish barely in view of one another. When one fish finds food, its behaviour, twisting, turning, and flashing, Will attract its neighbours to the area. Schools of cod, and other fish, are mainly kept together by sight and this is where the lure fishermen can score.

As I have said, cod are attracted by the flash and movement of other feeding fish. The signal sent out by a large swinging spoon or side-slipping pirk serves a double purpose. First, it will attract any cod within viewing range and second, it may look like food as the fish close in. Cod have large and well-developed eyes which they use to good advantage. At one time scientists believed that these fish were so dependent on vision that they were unable to feed in the dark. However, they have been shown to catch living food even in the total gloom of a photographic darkroom. Perhaps surprisingly, fish ‘tagged and tracked’ with tiny ultrasonic transmitters in their stomachs, remained almost stationary in the hours of daylight, even in the gloom of a fifteen-metre depth.

Pirking progress

In the early 1950s many fishermen used to fish for cod with ‘murderers’, the forerunners of modern jigs and pirks. The murderers were heavy pieces of lead-filled metal pipe or simply lead-bars fitted with big single hooks. The surfaces of the lures were polished or scraped with a knife until they shone, and the heavyweight attractors would be jigged up and down on hefty hand-lines. The cod were hooked either in the mouth or, quite often, in the outside of the jaws or head. Some big cod were caught by this method and no doubt it would still be effective, but for angling (and commercial fishing) purposes they have now been succeeded by the jigs, wedges and pirks introduced from North America and Scandinavia. The fashionable ‘butterfly jigs’ appear to be modern versions of the old murderer.

The principle of jigging a lure is best applied in situations where the angler can fish straight up and down into relatively deep water. The obvious places to try vertical jigging are boats, either drifting or at anchor, or from steep rock marks and piers. I have tried them from all these places with some success. My good pal Jon Bass visited Greenland many years ago and had some excellent sport with cod spinning, with a metal lure, from the rocks into deep water. Any sort of predatory fish may be caught on jigs, the method was not designed for cod alone.

My pal Jon (many years ago) spinning for cod in Greenland.

His catch! No digital cameras in those days.

Off the Pacific coast of Canada and the USA salmon are the main quarry of anglers jigging from steep rocky shores. They use a wide variety of pirks (they sometimes call them ‘diamond jigs’ – I suppose our equivalent is a ‘wedge’), many of them resembling the familiar ‘Prisma’. Some are drilled and slide freely on the line above the hook. There is probably not much to choose between the various types. The standard tactics involve a spinning rod and 12 to 15lb monofilament line (probably 30lb braid today), and a fixed spool reel with a large capacity: a 40lb King (Chinook) salmon with the entire Pacific Ocean in front of it can take a bit of stopping! When I tried the method out, during a brief business visit to British Columbia, I was entertained by two huge sea lions which were clearly after the same prey as me. I caught only a single, 7lb coho, or blackmouth salmon, using a white, 1.5oz pirk called a ‘Polar Bear’. The rocks from which I fished fell away into such a depth of water that I never managed to ‘find-bottom’, despite allowing the lure to sink with almost all my two-hundred metres of line.

The 'Polar Bear' a sliding form of wedge'.

A couple of years ago my good friend Alan Bulmer, from New Zealand, went to Canada and tried salmon fishing in the Pacific. Using a lure (a pirk) which was 3" long, he landed a 14 lb. Chinook. A stunning fish. As he said “Big Canadian fish like small lures as well...”

I asked him about his tactics -

“Were you fishing with the flasher in your picture? I made myself one after my trip to Vancouver Island years ago. I have never used it, but the principle is sound if you fish from boats anywhere. The commercial fishermen used to attach a plastic squid about a foot behind the wildly gyrating dinner plate. I had a coho from the rocks on a small silver pirk (similar to the one in your picture) when I was over there but I never caught a chinook.”

A flasher with the small lure trailed behind it.

...and he replied –

“The lures are attached about 18" behind the ‘plate’ (flasher). They never use big lures and catch salmon up to 38lb - on both hard bodied and squid types. Currently fish are only 7-14lb as it’s before main run.”

I'm always joking with Alan about the 'small' lures which he favours. Of course, different species of fish have preferences for prey of varying sizes so it's horses for courses. Fascinating stuff and I'd have really enjoyed fishing with my pal if it had been possible. There’s just too much fishing and not enough time for me to do it.

Alan had the last laugh with this cracking chinook salmon.

In Britain I have used pirks and wedges from piers and dinghies to catch cod, mackerel, pollack, coalfish, pouting, garfish and bass. It is often productive and convenient to fish a small silver pirk while waiting for a ‘run’ on conventional bottom tackle. The idea is to ‘find’ the sea-bed by lowering the pirk, and then to work it steadily back towards the water surface, sink and draw, until the fish are located. Remember that the fish will generally be nearer the surface at a dawn and dusk, particularly in settled, warm, calm weather.

The Danes and Norwegians often fish with pirks. Like the Canadian salmon anglers, they jig from steep rocks into deep water for cod, coalfish, and torsk. The technique involves a heavy terminal lure and a couple of droppers with plastic shrimps or squid's - a good method to use when exploring new territory (if there aren’t too many snags). The main lure can act either as a flasher to attract and stimulate predators to take the small accessory lures, or as a fish-catcher in its own right.

I have not fished for cod for many years, so there’s not much that I can add to what was said originally. I suppose that the ‘message’ is that these fish are fierce predators and often feed in social groups. The individual fish in a shoal will swim close enough to their neighbours that they can see if any nearby cod has found a source of food (hence the attraction of flashers and jigged lures).

Bass – shallow water specialists

Round South and West coasts of the British Isles the main summer species is the bass. Unlike the previous fish mentioned bass are really at home in shallow water and often need a different approach. At the opposite extreme to the heavy, vertical-fishing, deep water lures discussed so far, are the light-weight, shallow-diving, plug baits. Buoyant plugs can be designed or altered to fish at almost any depth, but among the most useful for bass fishing are those which dive to only a few centimetres or, at most, half-a-metre beneath the surface. Fast tides, shallow water, and snaggy sea-beds are the conditions under which these most fish-like lures come into their own. Wrasse, pollack and mackerel are also susceptible to these versatile gadgets.

Bass tails often show as they feed in shallow water - they are easily scared.

Buoyant, shallow-diving plugs are almost all armed with two or three treble hooks which makes them liable to rake up every fragment of weed or rubbish from the water (two, well placed, hooks are better than three which are liable to cause tangles and make fish difficult to unhook), and there is one massive advantage of this arrangement, the mid-body hook is ideally placed to take side-swiping predators such as bass, while the tail-treble will often nick into the rubbery lips of a wrasse or even a mullet which is trying to nip its tail. It is sometimes worth changing the tail hook for a smaller size and the mid-body one for a slightly larger or heavier duty one.

Bass often strike at the mid-body hook position of the lure.

Wrasse are usually tail nippers.

Since this was written the advantages of using surface lures and soft plastic-weedless lures for bass have become apparent, so it is worth setting them out here. The original benefits of the buoyant, shallow-diving plugs over most of the existing lures, lay in the fact that they float and so do not plunge into the rocky, weedy, snags of the sea-bed, after casting or if you stop winding. Secondly, on the retrieve, they dive only a little way and so fish over the top of any shallow snags. Thirdly they often closely resemble bass food items, and the bass love them.

All the above advantages of plugs are still present today, and they continue to catch lots of bass. However, they have been partly superseded in recent years by surface-popping and sliding lures which are similar but are designed to fish in the surface layer of water. When twitched or pulled, they cause a surface disturbance and so attract the bass from a distance. They also stimulate the fish to feed by splashing water from the dished face every time they are jerked forward (this resembles the behaviour of a leaping shoal of fry). The main disadvantage of these gadgets is that they tend to be most effective in the warmer, calmer period of the season and less so in the cold Spring and Autumn months.

The Skitterpop causes lots of spray and is a good surface-attractor.

I’ll describe the value of floating plugs by giving an account of a typical trip (long ago) to my own stretch of the Dorset coast. It was mid-summer, and, with our pals Terry Gledhill and Martin Williams, Harry and I had decided to make the pilgrimage to St Aldhelm’s Head. It was a fine, bright, calm sunny day, as we scrambled down the shale covered slope to the sea; followed by 20 minutes of exhausting progress over large, rugged boulders. As we reached ‘The Head’, the tide was flooding, and the fierce race was churning up white tops two-hundred metres offshore.

We each selected our personal boulders and began to cast the lures of our choice, Martin and I clipped on heavy spoons and tried (in vain) to belt them out to the edge of the race where the occasional mackerel could be seen leaping into the air. The other two tried plug fishing closer inshore, Terry with a big greenish Rebel plug and Harry with a Rapala J11. The early action was limited to a couple of mackerel hooked, and just as quickly lost, at maximum range on the metal lures.

After about an hour Martin switched to a Rapala and was quickly into a wrasse of reasonable size. As he hooked the fish, he gave a shout, so I laid down my rod and clambered across to help land it (the boulders being rugged and awkward). As we jointly pinned down, unhooked, and returned the 3lb, copper and yellow prize, Terry, perched on the biggest boulder in sight shouted “fish!” We looked up to see his Milbro-Ghillie, salmon-spinning rod well bent towards the sea.

Already rod-less, I picked up the communal landing net and again scrambling from rock to rock, went to Terry's assistance. I scaled the big boulder just as the grey and silver shape of a decent bass tore off on another run. The water boiled as the fish’s tail swept from side to side and pushed it towards a gap in the kelp. Terry swung the rod over to the side and steered his bass away from trouble. The fish plunged and thrashed, but now there was no escape from the nylon filament. It was drawn towards the rocks and into the folds of the waiting net. That fine bass weighed 6.5lb.

Much more versatile than plugs, poppers (or in my view any other lures) are the soft-plastic lures fitted with weedless hooks. These lures, which originated in the USA, were used in fishing for largemouth bass in snag ridden ponds and slow flowing rivers. They have a large, single hook with a cranked-shank, which positions the point of the hook flush with the upper surface of the lure, so that it doesn’t catch in most obstructions. Much as in the, plugs and the, ever popular (and very effective), Redgill or Eddystone type eels, the hook point lies about one third of the way back from the ‘snout’ of the lure; the ideal position for hooking side-swiping fish such as the bass. The hook point is only cleared and exposed when the jaws of a striking bass crush the soft plastic material. They are equally as good at penetrating the jaws of bass as the old types with exposed (snag-catching) hooks. A further major advantage of weedless soft-baits is the fact that they are relatively light-weight and so can be fished very slowly, even through wrack-beds and/or kelp stems. Many anglers forgo the benefit of fishing slowly by sliding a cone weight onto the nose of the lure to increase casting distances – a limited advantage unless the bass happen to be at long range.

An 18cm Evo-Redgill with its large, exposed hook is a good bass catcher. (but not much good through the kelp stems)

... but a slow moving, weedless, wriggling Slandra can be safely fished in weed and snags.

The Evo-stix lure is also weedless and weightless but could usefully be a bit larger..

As mentioned in the case of pike there is no doubt in my mind that bass caught on good-sized live or dead baits are, on average, considerably larger than those taken on lures. The evidence for this statement is now overwhelming. It seems probable that part of this difference is due to the relatively small size of the lures generally used. However, even fishing in the same places at the same times I have found that bass caught on natural baits are bigger than lure caught fish. This suggests that there may be an element of larger fish recognising lures as inedible; or even the rod-waving' behaviour of lure (or fly) fishermen, scaring bigger fish away. The inert, sit-and-wait bait angler may have an extra advantage.

The first example centres on a slightly deeper water (2-4m), shore, rock mark which, in many years of fishing with all the usual lures and flies has rarely produced a bass larger than 1.5kg (usually somewhat smaller) from literally hundreds of fish caught. As elsewhere the bass tend to be close to the shoreline, so distance is irrelevant. Here’s the description of my personal ‘epiphany’ when fishing this place:-

My next trip was to a rock mark (the one mentioned) where I expect to catch a range of fish species on spinning and fly gear. For ages we had been saying that “we should give live-baits a try for the bass at this spot” - largely because it is one of the few places where potential baits are often easily caught. Anyway, I lugged along my spinning rod, my fly rod and a ‘float rod’ set up in the same fashion that I use for pike fishing (but without the wire trace). The rig was simple - just a 4/0 circle hook and a split wine bottle cork for a float. No weights or swivels.

I've no picture of a pollack live-bait (they are a bit sluggish) but scad are better and mackerel are the best..

As usual, I set about fly fishing just before first light and, typically, my first catch was a bass of just over 2lb - it fought like stink. Then I had a smaller bass and a couple of small pollack. My third pollack was tiny (about 12cm) and I decided to try it for live bait. I hooked it through the top lip and plopped it into the sea; it seemed to be behaving itself, swimming round under the cork a couple of metres beyond the ledge. I felt that it was safe to pick the fly rod up again, so I laid down the float gear, opened the bale arm and left the little pollack to swim where it wanted. As I fly -fished I glanced occasionally at the cork to see that my bait was still OK. Suddenly, I looked, and the cork had gone – “the pollack must have pulled it under,” was my first thought. I picked up the rod and tried to lift the float - it wasn't there. I reeled in and it was only when I had recovered about thirty metres of line that I saw my float. The pollack was still on the hook - a bit the worse for wear, but alive. Could the culprit have been a bass?

Shortly after my abortive, possible 'bass run' I caught a modest mackerel on the fly. I replaced the pollack with the mackerel which promptly set off for the horizon dragging the cork behind it. No chance of laying the rod down with such an active bait; so, ignoring the fly tackle I decided to hold the float rod. After five minutes the mackerel was still powering away, but it had swum back to within ten metres of where I stood. Although it was quite capable of dragging my little float under there was no problem keeping in touch with the bait and the rapid vibrations transmitted through the rod and line showed me it was fit and well. Suddenly the cork ducked under more sharply and the line began to stream off my reel. This time it was just a steady powerful pull, quite different to the throbbing, tail beats of the mackerel.

I let the fish run for some time, in fact it probably took thirty or forty metres of line before I decided to tighten. My heart was in my mouth as I closed the bale arm and gently lifted the rod. It was on! The clutch buzzed as the fish took line against strong resistance. It was a few minutes before I had my bass close to the ledge. I 'beached' it on a wave and took my first decent look - well over 6lb and beautifully hooked in the scissors. The whole scenario (apart from the long initial run) was just like the ones I had experienced many times with pike. Was I pleased?

Mackerel lip-hooked on a big circle hook will 'search the water' for hours and don't need a float.

So, the bass was much heavier than any that we had ever caught on flies or lures from that spot – ‘one swallow doesn’t make a summer’ but surely not a coincidence. Anyway, I decided there and then to try the technique again, just to prove the point. In the next few weeks, I had a couple more goes - both short (1-1.5 hour) early morning sessions. I geared up to catch bait with a small, single-hooked Toby on the end and an uptrace Mylar fly. On the first attempt it was pretty rough (=dangerous) and I could not buy a bite from mackerel. Eventually I hooked a garfish on the fly but by then it was time for me to go home so I released the gar.

I went again the following morning and found the sea much calmer. The wind had eased, and the swell had gone down. The tide was just beginning to rise when I started fishing at about 06:15. After about ten minutes I had a couple of feeble bites (?garfish?) and then hooked a splashy little fish which turned out to be a small school bass which had taken the Toby, it fell off into a rockpool, so I cast again and promptly hooked a small pollack of about 20cm long. I took a picture of the two fish, released the bass, and put the pollack on the live-bait rod (as before - circle hook and wine bottle cork(s) float).

The pollack swam round gamely for about fifteen minutes and nothing happened so I picked up the spinning rod and had another cast. First chuck the Toby was taken by a mackerel which I reeled in and used as a replacement for the lethargic pollack. By now I was looking at my watch and thinking it was about time I packed in. However, I lowered the mackerel into the sea and let it swim off. For the next ten minutes it ploughed along towing the corks behind it and occasionally splashing on the surface. Suddenly I felt a hard knock on the rod and the line began to stream off the spool. As I had done before I let the fish take a lot of line before I closed the bale arm and tightened - it was on!

What a good scrap; not least when I had to land the bass by jumping down onto a lower ledge already awash with the swell. The fish was perfectly hooked in the upper lip and was in fine fat condition. I weighed it (unusual for me) and it proved to be over 11lb. Live mackerel baits - now I was convinced! Since those events, my pals and I have had more good bass on live mackerel from that spot. None of them has been smaller than about 5lb. We have, however, had a great many more bass on lures and flies (all of them small). The only change in my live-baiting technique is that I discovered that there is no need for a cork (or any other float) on the line. The mackerel rarely go to ground unless they are exhausted, but of course it is essential to hold the rod at all times.

A fine bass taken on a live mackerel.

In fishing for bass, particularly from steep rocks into deeper water, mackerel, garfish and scad are all potential catches on lures. My experience suggests that, despite their reputations as easy catches, all three can be distinctly fussy about what they eat.

The fastidious mackerel

Mackerel, will without doubt, take almost anything that moves when they're in a feeding frenzy. Because of this, and because of their desirability as bait, the methods developed for their capture are decidedly crude. Feathers tied on hooks stout enough for skate or conger and jigged or trailed on strings of nylon-monofilament thick enough to cope with ‘Jaws’. Why is it that a species of fish the size of a dace or roach can be so suicidal?

Even using a string of feathers, it is often obvious that one lure is favoured by the fish. This is particularly clear if a small spoon or mackerel spinner is tied to the end of the string and if the mackerel are few and far between. The metal lure will frequently out-fish the feathers ten to one. A small strip of mackerel skin will also enhance the attraction of a lure, so even in the turmoil of thrashing fish and whisking hooks the mackerel are able to pick and choose.

Three further lessons may be learned from the mackerel enthusiasts.

1. Multi-lured tackles may attract fish to the area.

2. A hooked fish will attract others to neighbouring lures, and -

3. A thick line and trace do not always deter fish from biting.

The selective ability of mackerel soon becomes apparent when float-fished baits are used to catch them. Many years ago, when I fished for mackerel at Plymouth under the tuition of a local ‘expert’ from the Marine Biological Association, I was shown how, even a carefully trimmed strip of mackerel skin was inferior to freshly caught ‘brit’ when it came to producing bites.

In terms of spinning, I have landed mackerel on most types of lures. Flies, plugs, spoons, spinners, pirks, and even hookless lead weights (no hook – in through the mouth and out through the gill opening) on a couple of occasions, have all tempted fish. Nevertheless, the basic principles of spinning with artificials should be followed. The movement, size, shape, colour, and swimming depth of the natural food (often small, silvery fish) should be copied as closely as possible.

A plug-caught mackerel and the sprat which it coughed up.

At dusk, the fish and their prey tend to gather near the sea-surface, particularly in periods of warm, calm weather, and this is where to seek them. Often the spots where they congregate are quite local and can only be learned by experience. Deep-water races are pretty reliable but even quite shallow, sheltered bays and gravel storm beaches will sometimes prove productive, a good example being the shingly, cliff-bound cove of Chapmans Poole in Dorset, where I have often caught these fish.

Again, in our area, the famous Chesil Beach is noted as a source of mackerel in abundance. Most are caught by long-casters using heavy leads and strings of feathers but spinning gear and a single lure will also give plenty of sport-if you can find enough elbow room to use them without being anti-social to the ‘serious’ fishermen!

An early morning mackerel taken in the dark on a luminous spinner.

This brings us to the question of catching mackerel on single lures. The two main characteristics of the species to be considered are its amazing vitality and its brittle mouth. Many angling writers have commented on the fighting qualities of these little fish, but relatively few anglers take advantage of this ‘sport potential’ in choosing their tackle. Trolling under power makes it practically impossible to fish with sensible gear. The drag on spinning tackle at a trolling speed of only one or two knots is ridiculous and, when a fish is hooked, most of the fight is hauled out of it before the ‘way’ has been taken off the boat.

Single-hooked, metal lures do less damage to the mouths of mackerel used as baits.

The only way to appreciate the power of these mini-tuna is to fish from the shore or from a stationary or drifting boat. A lure appropriate to the conditions and swimming depth of the fish, cast or jigged on braided line (it might as well be 20 or 30lb braid, in case of accidental bass or pollack), will give fantastic sport. Why such heavy line? Well, subject to hooking the fish, the clutch setting can be as light as you want, so the battle will be the same. Also, the brittle mouth of the fish gives no sound hold for tiny hooks and a sensible compromise is a fair sized (2 to 6) treble or single hook and a rod and line suitable to hook the fish firmly. Perhaps the best argument for strong line is that it often allows you to rescue lures from kelp and other snags.

Mackerel can be caught in quantity on fly tackle. Like many other predatory fish they tend to rise towards the surface of the sea in the hours of darkness. In fact dawn and dusk are the prime times to catch these fish. A #7 or #8wt fly rod with a floating line is ideal, and a mono leader of about 6lb B.S. armed with a small, flashy fly or (my preference) a small Delta type plastic eel on a stainless hook will often catch fish after fish. The sport can be hectic.

Mackerel are wonderful sport on fly gear.

Garfish and scad

Both garfish and scad are, at times, caught by anglers fishing for mackerel and indeed the two species have much in common, but neither is quite such a sucker for artificial lures as the mackerel itself. The mere shape of the gar’s mouth is enough to suggest that it might be difficult to hook firmly - and indeed it is, often breaking free following a few lightning rushes or a skittering leap. The scad is less of a fish-eater than either of the others and is much more likely to fall to a float-fished worm. Even scad, however, can be caught in very large numbers by spinning methods or on flies, as mentioned for mackerel. On one occasion Harry landed one scad after another on a small Mepps. He was fishing from the shingle beach of Chapman's pool in the late evening in September; all the fish were returned alive to the water. Scad will feed well into darkness and I have caught large numbers on Mepps-type lures adorned with a luminous (Beta-Lite) body.

A fly-caught garfish. Even on a fly they are tricky to hook.

Scad take small eels and shads on fly tackle too.

My old pal Dave with a fly-caught scad.

Luminous spinners lure scad in the dark.

Save our sea fish!

These are the main species of predatory sea fish taken on lures around our coasts. The tackle and tactics used are not very different from those which catch game and coarse fish in rivers and lakes. The basic idea is to fish with a rod, reel, and line appropriate to the conditions being fished, using lures designed to attract the species which are sought. Sea fish are no easier and no more difficult to catch than any others, and to succeed, everything needs to be correct. When success comes it may be very, very satisfying, because many species form large schools.

In fact, I think spinning for sea fish is exactly the same as spinning for coarse or game fish. If there are no fish, you will not catch any! If the conditions are wrong, you will not catch any! If you are using a lure which is unsuitable, you will have very few bites! However, before ending, I feel obliged to make a serious plea to all anglers. If you are fortunate enough to find the correct combination of fish, conditions, lures, tackle, and tactics, you may be able to catch exceptionally large numbers of fish. If you need them to eat, to feed your family or to fill your freezer with food or bait, fair enough-but please return unwanted fish to the sea alive and well. If you dump them on the beach, bury them in the garden or even sell them for profit, then you are endangering the future of angling as a sport. Quite apart from the possible depletion of stocks by your efforts, there are those who (wrongly, in my view) see angling as a cruel and greedy sport. We should do nothing to encourage this impression.

In fact, one of the best ways to justify angling (if you ever feel that you need to) is that, unlike most commercial fishing methods; it is possible for us to select almost exactly what we want to catch (so there is no bycatch) and, if there are accidental bycatches or if you catch young, undersized fish, they can be (and are) returned unharmed to the water.

– PLEASE TELL YOUR TWITTER, FACEBOOK, EMAIL FRIENDS ABOUT THESE BOOKS.

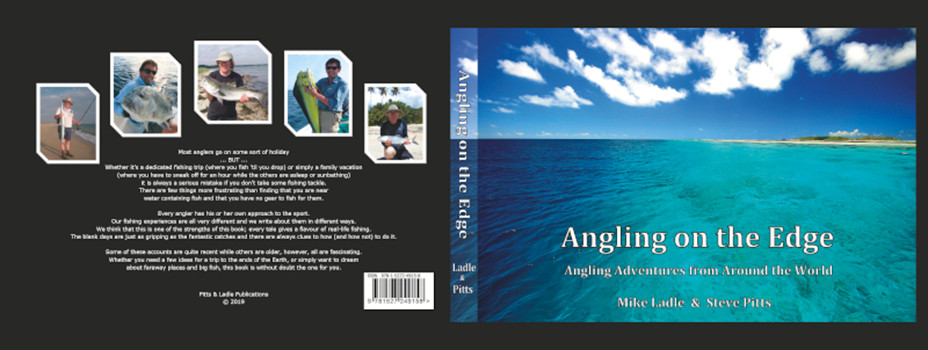

ANGLING ON THE EDGE

Copies can now be ordered (printed on demand) from Steve Pitts at £34.00, inc. Royal Mail Insured UK Mainland Postage.

To order a book send an E-MAIL to - stevejpitts@gmail.com

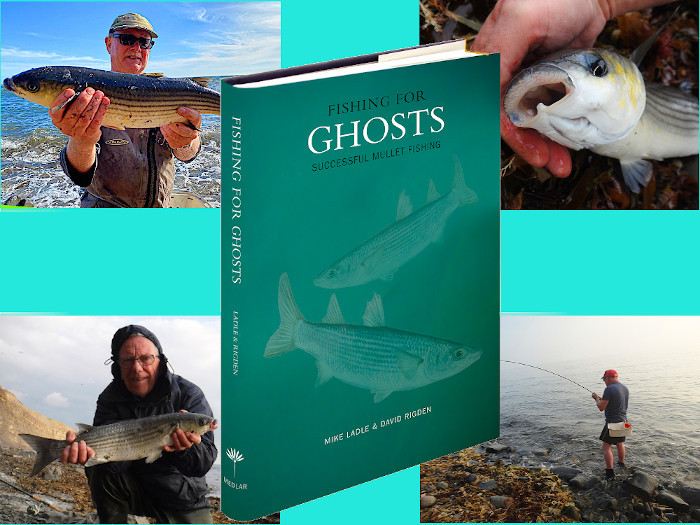

FISHING FOR GHOSTS

Written with David Rigden. Copies from

THE SECOND WAVE

Written with Steve Pitts this is a SEQUEL TO THE BESTSELLER "Operation Sea Angler" IT'S AVAILABLE ON PAPER FROM -

If you have any comments or questions about fish, methods, tactics or 'what have you!' get in touch with me by sending an E-MAIL to - docladle@hotmail.com