Catch Fish with

Mike Ladle

Information Page

SEA FISHING

For anyone unfamiliar with the site always check the FRESHWATER, SALTWATER and TACK-TICS pages. The Saltwater page now extends back as a record of over several years of (mostly) sea fishing and may be a useful guide as to when to fish. The Freshwater stuff is also up to date now. I keep adding to both. These pages are effectively my diary and the latest will usually be about fishing in the previous day or two. As you see I also add the odd piece from my friends and correspondents if I've not been doing much. The Tactics pages which are chiefly 'how I do it' plus a bit of science are also updated regularly and (I think) worth a read (the earlier ones are mostly tackle and 'how to do it' stuff).

Lure fishing in the 2020s - Part VIII

Baited-lures and part-time predators.

Select your species!

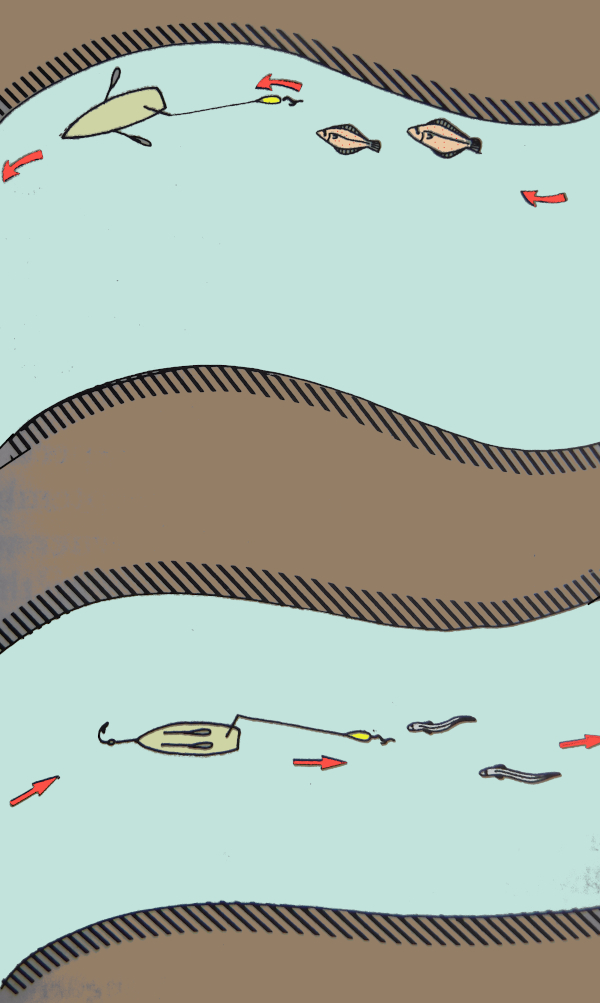

Having written about the advantages of spinning which arise from the freedom from buying or collecting bait, it may seem strange to suggest that the addition of natural bait to artificial lures could improve catches. However, John Garrad in his book, ‘Sea Angling with the Baited Spoon’, showed that the spoon, garnished with bait, could tempt some surprising catches. Two important points were revealed by Garrad's experiments in the Hamble estuary: Firstly, differences in presentation of the spoon were important, so that spoons trolled 'with the current' only caught flounders and spoons drifted 'against the current' only caught eels: Secondly, the type of bait used did not seem to matter very much. The last point is pretty fundamental since, as most anglers are well aware, both eels and flounders can be very fussy about baits fished on normal tackle.

Flounders take baited spoons trolled with the flow and eels take them drifted from anchor against the flow.

A flounder taken on a ragworm-baited-spinner, from the shore.

Garrad fished only for flounders, eels, and school bass, but he mentioned quite a few accidental catches to anglers using his methods; wrasse, pouting, plaice, dabs and so on. Perhaps the first real addition to his exciting discoveries came from another South-coast estuary at Christchurch. Anglers, fishing Christchurch Harbour, in the outflow of the Rivers Stour and Avon, discovered that the attachment of an inch or two of ragworm to a small spinner, resulted in amazing catches of grey mullet. The mullet, mostly freshwater-loving thinlips, seemed to find the combination of spinning blade and ragworm irresistible, and impressive catches were reported by devotees of the method. Curiously, that enthusiasm has not really spread to other areas.

Thinlips often compete for baited spinners as though they hadn't eaten for months.

On our own stretch of the Dorset coast thick-lipped mullet are frequently taken by anglers using a variety of methods and baits. Having been convinced of the ‘Christchurch Story’ by one of my pals, Steve Pitts, I decided to see whether the baited spoon would work for the local thicklips. Steve gave me a few of his secret weapons; ultra-light ‘Jen-spoon’ spinners, resembling Mepps but with the shafts adorned with red plastic beads instead of a brass weight. The entire structure is so light-weight that it is quite unsuitable for normal spinning, because the blade, the bar and the hooks all turn actively together and can cause horrendous line twist. The addition of bait to the treble hook damped down this rotation and added a little casting-weight to the lure.

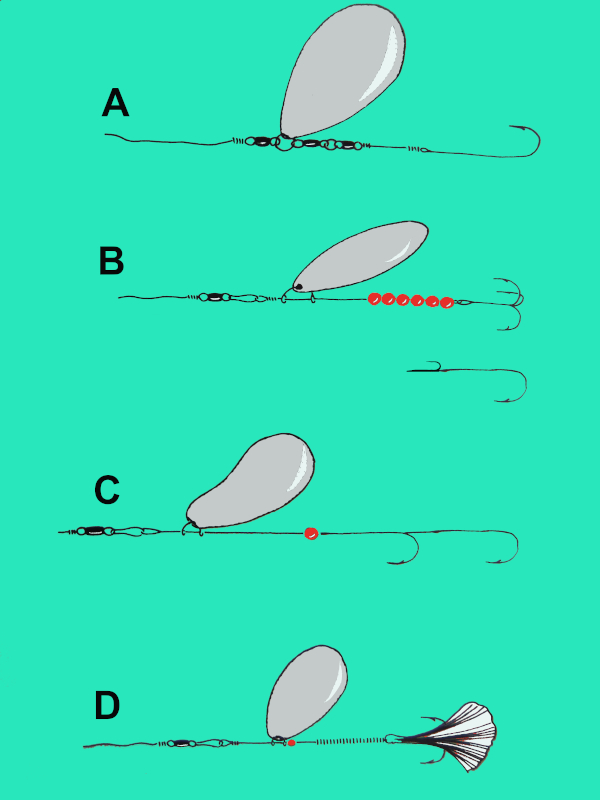

A Flounder spoon B Mullet spoon (spinner) (showing improved hook-rig below) C Gurnard spoon (as used by Dr Kennedy) D Roach spoon (used in Holland)

Tempting a thicklip

The best way to describe the method of fishing with these spoons is probably to give an account of my own experiments. Steve had told me the basics - “when you feel a bite, just keep reeling, etc. etc.” - and he had regaled me with tales of large catches of smallish fish (1-2lb); “one-a-cast” is a phrase which springs to mind. Armed with this information from the ‘expert’ I drove down to my local rocky-shore on a spring tide in September. Very few mullet were showing in the sheltered corner which I had chosen to fish, so I was not tempted to set up the fly rod. My tackle was an eleven-foot, through-action, carbon, carp- rod and a Mitchell fixed-spool reel, loaded with six-pound, monofilament line. The ‘Jen-spoon’ was clipped onto a tiny link-swivel and three inches of ragworm was suspended from the treble hook. I swung the lure out and, lifting the rod tip, watched the silver blade flutter along, just beneath the surface. I stood by the edge of the calm sea and cast the lure five-or-six metres out from the margin. After allowing the spoon and worm to sink for a second or two I began a slow retrieve, with the rod point few inches above the water. There was of course no response, and a further dozen or more casts met with the same result. Then a couple of mullet swirled, close in and some distance to my left. I swung the rod again and the spoon plopped into the sea, beyond the fish and about 1m out from the beach.

As the slow retrieve started, I felt something gently plucking at the bait. I continued to wind steadily, and the plucking persisted almost until the lure finally emerged from the water and swung freely from the tip ring. The plucking sensation was repeated on the following cast and, intermittently, on several of the next half-dozen.

By now several thoughts were running through my mind. The bites (I was sure they were bites) must be mullet! Why had I not made contact? Despite what I'd been advised, I even tried a couple of sharp strikes without the slightest hint of a fish. Was the section of worm the right size? The first fish, on any unfamiliar method, is always the most difficult. Pushing the loss of confidence to the back of my mind I continued to fish in the same way as before. At least I was getting bites, and it is never wise to change tactics without giving each method a decent trial period.

Half-an-hour and innumerable plucks later despair was beginning to set in but, just as a change of tackle was imminent, success! A bite developed at the first few turns of the reel and the culprit seemed very determined. As the lure approached my feet, I could just see the grey shape of a following mullet, sucking and plucking at the trailing worm. The slight swell was swirling around a prominent rock which stood just clear of the water and, when the spoon and its follower entered the swirl, there was a sudden heavy pull and I found myself firmly attached to a hard-fighting mullet. The fish tore about violently and, in the way of most mullet, refused to give up, but eventually it was netted and weighed in; three-and-a-half pounds.

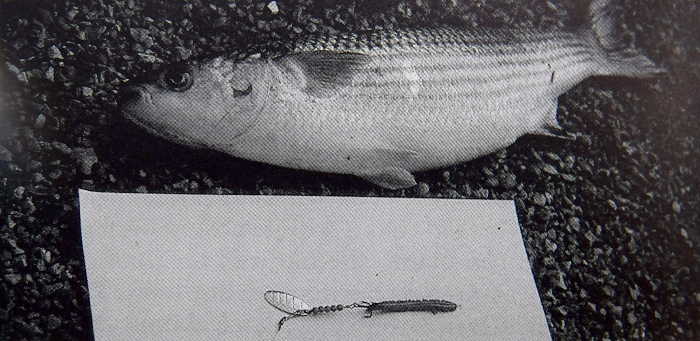

Thicklip taken on a ragworm-baited Jen-spoon. The treble hook was soon dispensed with.

Despite my persistence there was only one further event in the session. Several additional bites occurred, all apparently identical. However, shortly after the capture of the thicklip, as the lure was lifted from the sea, a second fish - a 6” sand-smelt - hooked itself. As already mentioned, the bites of the two species were indistinguishable despite the great difference in size and fighting capabilities; the little sand-smelt was swung ‘to hand’ like a tiny roach or dace.

So, three more species were added to Garrad’s list for the baited spoon; thin- and thick-lipped mullet and sand-smelt. In all his years of experimenting, he did in fact report a single ‘mullet’ caught from ‘Garrad’s creek’ on a 3” flounder spoon. The significant thing is that while fish such as mullet, eels and flounders, can be caught in large numbers on baited lures (numbers often far in excess of the results from conventional bait fishing) few, if any, would be taken in many hours of spinning with unbaited lures.

Surface feeding mullet sometimes take small, unbaited lures - but maggot-flies or bread baits are generally better.

Some other spoon-fed fish

Garrad lists quite a few ‘extra’ species caught (by his correspondents) on baited flounder spoons; these included haddock, pollack, wrasse, red-gurnard and plaice. On charter trips Harry used to use a large baited-spoon as an attractor, often to out-fish other anglers after plaice – nothing too unusual about that perhaps – but, in the course of catching the plaice he also took a red gurnard on the worm-baited spoon. In fact, this recalls the use of a baited, kidney-shaped, bar spoon by Dr Michael Kennedy, specifically for catching gurnard (grey ones in this case). Although Dr Kennedy gives no details of the method, in his excellent book ‘The Sea Anglers Fishes’, he does comment that the eleven gurnard he illustrated were taken in a single catch “from the shore”. Match anglers (and others) interested in big bags of fish from the shore could certainly do worse than experiment with baited spoon tactics.

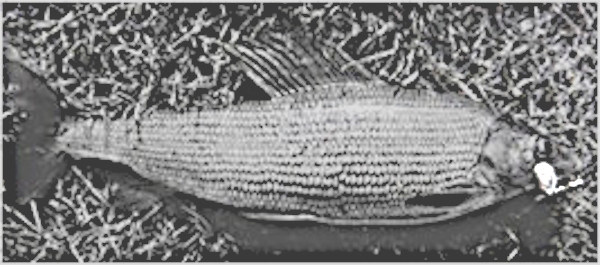

Grey gurnard taken on a baited spinner by the late Dr Michael Kennedy.

One other point of interest which relates to the use of baited lures was suggested by my friend, Dave Cooling. Dave has done quite a bit of wreck fishing. Much of this fishing was for large predatory fish and involved various methods of presenting artificial lures - pirks, Muppets, Redgills and so on. Dave said that these methods may be just a selective as the flounder and mullet tactics described earlier. A simple unbaited pirk tended to catch Cod; the addition of a mackerel strip to a similar lure often resulted in the capture of ling; and a rubber eel on along trace, over the same wreck, may attract pollack and coalfish. Here then, are the seeds of more experiment and improvement.

The addition of bait to a spinner is not simply a matter of hedging-your-bets against failure of one or other approach (as is the case with most cocktail baits’). It is a totally different way of fishing, enabling you to make good catches of worthwhile fish when other methods might fail or, at best, be far inferior. American anglers are absolute fanatics for adorning their lures with rubber worms, feathers, rubber squid, lumps of pork rind, and so on. Our transatlantic cousins obviously think that these additions are worthwhile; clearly, they are at times obtaining good results, but we have yet to see (despite much reading) any reasoned explanation as to why any such additives should be more attractive than the others.

Schooled to take a lure.

Before considering how to extend the possibilities of baited lure fishing it is worth considering why fish such as mullet should take a lure at all. These fish usually feed on algae or other tiny particles and, although they will occasionally nip at a plug or spoon, they normally decline to bite. Mullet are, first-and-foremost, schooling fish with a strong ‘group instinct’. Experiments have shown that the presence of a single feeding mullet stimulates every other fish that sees it into a frenzy of feeding activity.

In many schooling species, when one fish in a shoal has found an item of food (e.g., a worm) all the others want a share, and chase after the ‘lucky finder’ in an effort to pinch its prize. Possibly the baited spinner looks like a smaller fish carrying a desirable morsel, and the mullet try to make it give up its prey by bullying it. In the bird world, not only do members of a flock squabble for delicacies (note the way that chickens chase and fight over a worm) but, sea birds like skuas and herring gulls will obtain much of their food by pestering and robbing weaker species (it is presumably easier than catching it themselves). If this idea is correct, many schooling fish may be susceptible to the attractions of a baited spoon.

To widen the field a little more, I recall that Richard Walker in his book ‘Still Water Angling’, illustrated some very large roach (possibly hybrids?) which had been caught on lightweight spinners armed with small trebles, set well to the rear of the blade, and decorated with feathers. Apparently, the fish were susceptible to these ‘feather-baited’ spoons in the early part of the coarse fishing season. I cannot fail to be struck by the similarity between these roach-fishing tactics and the mullet spinning methods already described. It seems certain that the principle is the same in both cases. An angler with initiative, patience and access to waters where shoaling roach, or other fish of the carp family, grow to a good size, could possibly produce spectacular catches by developing his own mini, lightweight, long-shanked, worm- or maggot-baited spinners. The technique will probably involve a longish rod for optimum lure control, lines of 3 to 6lb breaking strain on a fixed spool reel, and a very slow retrieve. The approach will be ‘suck-it-and-see’. This seems to me to be one of the more exciting challenges in angling; for while I have now caught such unlikely species as dace, rudd and bream on small, unbaited spinners, heaven knows what I might have tempted if I’d had the foresight to add bait to the hooks. Here indeed is scope for research.

To return to the subject of grey mullet. The thinlip is the one (of three, common, UK species) which is really susceptible to a baited spinner. My pals and I have now caught a great many of these fish from local rivers and estuaries on traditional ragworm-baited spinners.

A nice thinlip from freshwater on a rag-baited spinner .

School bass readily take a baited mullet spinner (this one has a weighted shaft to aid casting).

Perch are also susceptible to baited 'mullet' spinners.

It is possible that the addition of suitably edible morsels might improve results with some of these. Secondly, there are species such as rudd, bream, dace, wrasse, plaice and the like which will take baited lures but could probably be caught in larger numbers by the use of traditional baits. In this case there is just a possibility that the addition of a spinning lure might enhance catches, in terms of fish-sizes or numbers.

Wrasse like a spot of meat with their metal.

This was one of several rudd taken while spinning for thinlips in my local estuary.

Lastly, there are a few species such as thin-lipped mullet and flounder which definitely take much more freely when a lure is enhanced by the addition of a suitable bait.

Since the original publication of this book, in the 1980s, I’ve caught a lot more thinlips. These fish are suckers for a baited spinner. In fact it can be so successful that it is sometimes (wrongly I think) frowned upon by some of the more ‘traditional’ mullet anglers. Ragworm seems to the best bait although clams, earthworms and cooked-prawns all attract bites. Perhaps the most interesting thing is the way that the fish feed well even in fresh water. I’ve caught large numbers of them several miles above the tide on my local rivers (as well as in the estuaries and in harbours). In the clear water of the river I’ve been able to bait and try out different types of ‘spinner’ (including Devon minnows and plugs). I usually switched the traditional treble hooks to a single hook with a smaller retaining hook above it to stop the bait sliding down and masking the point.

Part-time predators and unbaited lures

Other part-time predators are much more susceptible to lures than the above species. I should probably have placed chub in the next chapter, however, I've left them here, as in the original book. Chub, barbel and grayling are sometimes caught on unbaited lures being used for other fish. I have (very occasionally, many years ago) landed respectable barbel on wooden Devons intended for salmon and the capture, also in years past, of barbel up to record size (fourteen-pounds plus) by anglers spinning for salmon is well documented. The barbel with its under-shot, whiskery mouth, does not seem much like a predator but the chub, in contrast, looks rather like a living coal-scuttle, prepared to eat almost anything. A great many chub, of all sizes have fallen to unconventional baits and tackle. In years gone by, when Harry and I used to regularly fish the Dorset Stour, we caught quite a few on small spoons, spinners and plugs.

Chub eat most things and large ones will take lures keenly.

When we were first preparing this book, in the 1980’s, I had a letter from a friend, Bob Spurgeon, who, at that time, had taken things a bit further. I quote from Bob’s letter: -

"As you are interested in spinning (for coarse fish) in freshwater I will expand a little more on my experiences. I have been fishing in the Bath area now for over 20 years, and over these years I have tried many different approaches, by nature I tend to pick a method and fully explore its potential for a whole season. This year I was determined to give plugs try.”

“I have been using small spinners for years, usually presented without a trace on four-pound nylon line, fixed spool reel and a 10’, Mark IV (fibreglass) rod ... In my early days I regularly caught perch (to 1.5lb) and chub (of similar size) using this gear, but some of the chub were quite small.” “Last year, when I returned to lure fishing, it was specifically to try plugs and not spoons or spinners. The first thing I had to do was to find if they would catch anything at all and so, in early April, I fished a Rapala, 5cm GFR (a floater) downstream in very blustery weather and on the retrieve, took my first plug-caught trout, a rainbow, (the first of many on that lure) ...”

“Now, a few notes on the species – “

“Chub - I'll put these first as they are my main quarry at the moment. The plug is definitely selective of the larger fish and not, I think, purely as a predatory thing (I find that most of my live minnows end up being scoffed by fish of about half-a-pound; It is rare to take one that small on the plug). Most chub strike the plug almost immediately, I guess it needs to intrude on their territory suddenly to be effective. That is not to say that they will not turn and follow it for a while, but a steadily retrieved plug, pulled across the shoal, is no good, it needs to be splashed in amongst them. Many takes are almost instantaneous, bearing that in mind I feel that pattern and coloration are not important.

“Perch - there are no large perch left in my River, following their disappearance several years ago, but there are quite a few smaller ones. These little fish (up to half-a-pound but biggest at 1lb) always engulf the plug from behind. They are not very good at it and a steady retrieve is required for them to be successful.”

Bob’s comments largely agree with my own observations. Grayling, like chub, will readily take spinning lures. In rivers up around the Arctic Circle the use of spinners is a standard method of catching these fish. Chalk-stream grayling are not much different from their northern relatives and a Mepps-type spinner, fished slowly down and across, will sometimes attract a large specimen. In this respect the spinning lure may again select for the better fish.

Decent grayling will take spinners but bait fishing is much more effective.

It should, by now, be obvious that the capture of large coarse fish on plugs, spoons and spinners is no accident and that anglers with the approach and application shown by Bob, are on the verge of a considerable breakthrough in techniques. “Why,” you may ask, “have spinning tactics not been developed already if they have so much potential?” I gave the answer earlier, but it is worth repeating. By tradition, many British anglers have no faith in artificial lures, baited or unbaited. Only when enough anglers devote sufficient effort to developing these methods will they begin to appreciate the possibilities. (This is no longer such a problem and I know many anglers who regularly spin for all types of fish).

Since the 1980s, I have done a lot more spinning with lures in Dorset rivers. Chub, perch, pike, trout, seatrout, and salmon have all been frequent catches on my unbaited artificials. Of course, I had previously caught these fish on lures but now I regard plugs and (more recently) softbaits as an essential approach to the capture of several species. I’ll finish this chapter with a few more thoughts on chub.

Chub

There is no doubt that chub are omnivorous fish, so they like a bit of meat with their veg if they can get it. They are commonly caught on bread, seed, and meat baits as well as worms, slugs, insects, and small fish. Plugs, however, can be highly effective and even quite large lures (say 11cm in length) will catch chub of all sizes. Colour doesn’t seem to be too important, and it is rare to need a lure which fishes deep, so buoyant, shallow-diving versions are pretty effective. I still tend to stick to a simple, jointed, 7cm or 9cm, black and silver Rapala. Even the smaller plug, which weighs only 4g, (the J9 weighs 6g) will cast well on my braided lines, and I suppose that, if I was specialising, I could settle for a lighter braid than my usual 20lb Whiplash. However, chub like overhanging cover so it is always going to be necessary to yank the lure free of bank-side snags occasionally, and the universal presence of pike means that a wire trace (15-20lb, knottable, AFW in my case) is essential.

Small chub can be tempted by fair-sized plugs.

My grandson Ben (now a lot taller than me) enjoyed spinning for chub when he was younger.

Chub are beautiful fish even if they can be a bit lethargic.

The fish don’t appear to be put off by the ‘heavy’ tackle or the wire, and the most difficult thing is often to get a lure to them without disturbing them first. As Bob Spurgeon suggested, big fish are often caught on the small plugs and they will frequently take them almost as they hit the water. The big advantage of spinning is that it is a very mobile approach. There is no need to carry bait or anything other than your rod, a couple of lures, and a net. Simply flick the plug into any likely spot and wind it back. On the Dorset Stour, where I’ve done most of my plugging for these fish, they will quite often follow the lure for some metres before taking – which might be related to the lively attraction of the jointed plugs.

Snaggy banks are a good incentive to use relatively cheap plugs..

Plugs can easily be fished by casting either downstream and slowly retrieving against the flow or casting upstream and simply winding back. I can’t say that chub, of any size put up a great struggle to escape (this is not a result of the strong line, as the clutch setting can be as light as you want) but they are big, beautiful fish and always a pleasure to catch.

– PLEASE TELL YOUR TWITTER, FACEBOOK, EMAIL FRIENDS ABOUT THESE BOOKS.

ANGLING ON THE EDGE

Copies can now be ordered (printed on demand) from Steve Pitts at £34.00, inc. Royal Mail Insured UK Mainland Postage.

To order a book send an E-MAIL to - stevejpitts@gmail.com

FISHING FOR GHOSTS

Written with David Rigden. Copies from

THE SECOND WAVE

Written with Steve Pitts this is a SEQUEL TO THE BESTSELLER "Operation Sea Angler" IT'S AVAILABLE ON PAPER FROM -

If you have any comments or questions about fish, methods, tactics or 'what have you!' get in touch with me by sending an E-MAIL to - docladle@hotmail.com