Information Page.

"Fish parasites."

Some years ago I wrote this piece in response to a letter to a magazine from an angler concerned about the state of the whiting which he was catching. In his words - "many fish seem to have a (purple swollen) growth on their gills." and the fish which were affected were only "half the weight of healthy fish." This is a perfect description of the symptoms of a little parasite with a long name - Lernaeocera branchialis.

Lernaeocera is one of the more bizarre creatures to inhabit the sea and although its body looks like a little banana shaped bag of blood, it is in fact a crustacean, distantly related to crabs and lobsters. A great many of the fish parasites in the sea are crustaceans - either barnacles, wood lice or copepods (I’ll call these ‘fish lice’ just for simplicity). Their free living cousins are key elements in the food chain of the sea but the parasites are much more fascinating, in a sinister sort of way.

I guess that most experienced sea anglers will have noticed sea lice on their catches. Look carefully at the next fish you catch, that little transparent "loose scale" which scuttles away when you touch it is certainly a fish louse. Different parasites have preferences for particular species of fish and even for special parts of the fishes' body.

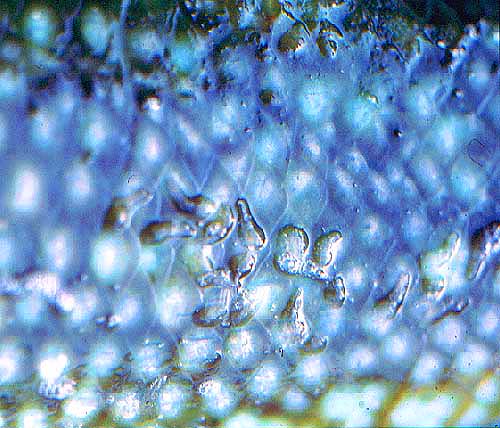

The ballan wrasse which I catch almost always have lots of creeping sidling fish lice on their flanks. As I unhook a bass it is unusual not to notice little flattened louse type parasites clambering about inside its mouth. That lump on the shoulder of your specimen corkwing wrasse, believe it or not, contains a parasitic crustacean. The parasite hordes are EVERYWHERE.

A typical fish louse is flattened and streamlined and presses close to the skin of the fish - to avoid being washed or scraped off. The common Caligus is a good swimmer and can move from fish to fish. It is not too fussy what sort of fish it lives on. When mature it will carry a pair of the elongated, sausage like egg sacs characteristic of all copepods whether free living or parasitic.

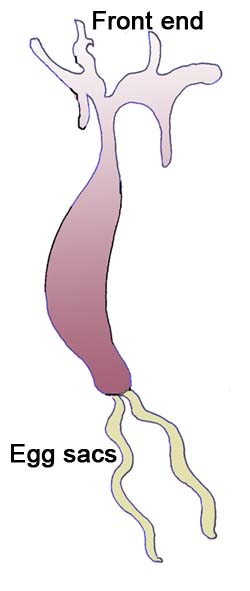

Many fish lice look nothing like Caligus. Millions of years of evolution have adapted them to their hosts in strange ways, but however odd and distorted the body shape may be the two hanging egg sacs are always a dead give away. When the eggs are released from their sacs they must of course find a new host. Lets just follow one of the thousands of eggs produced by the little monster that was on the whiting’s gills as it goes through life.

After hatching the tiny larva swims free in the open sea. If it is lucky enough to avoid the filtering gills of mussels and oysters and the countless hungry mouths of the plankton it will seek the safety of a new host. Not, as you might think a whiting but a plaice, a flounder or a dab. Attached by its antennae the parasite glues itself; head first, to the gill. Snuggling into the gill filaments of the flatfish our tiny copepod now takes a hearty meal of blood from the riches all around it. After fattening up for a while our baby enters a resting stage. After a while the skin bursts open (shades of "Alien") and out pops a free swimming adult stage.

If it is a male the fish louse finds a partner, mates and dies. If, on the other hand, it is female, after mating it swims about looking for a whiting, a plaice, a flounder or a cod. Having found its final resting place in the gill chamber of the whiting a wonderful transformation takes place. The head sends out feeding roots into the gill tissues of its fishy host. The body turns into a chubby purple bag and the swimming legs and other appendages are all lost. Two long curly egg sacs develop and the fish louse becomes simply a greedy, parasitic, egg factory. So greedily does it turn fish-blood into parasite-eggs that the host whiting is often reduced to a mere shadow of its former self. This LOSS OF CONDITION is typical of fish carrying these parasites and none of us would want to catch, let alone eat, such manky specimens.

There are thousands of other parasites on fish. Another species of Lernaeocera attacks haddock and lemon sole. A similar creature anchors itself into the eye sockets of sprats. Its long, tube like body and its two trailing egg containers often reach to more than half the length of the unfortunate fish. In addition to fish lice and their relatives fish are subject to all sorts of lodgers. Those brown strings in your cod fillet or bass steak are probably round worms. Leeches, lampreys and hag fish bore through even the tough hides of skates and sharks. Flukes suck blood from the tender gills of many sea fishes and protozoans and tapeworms infest virtually every possible organ in the body.

In recent years fishing in the tropics has introduced me to a number of nasties that I had never met before. When wading on the flats me and my pals have had our legs bitten by little fish lice. They were small and white and had jaws strong enough to nip and draw blood. Also, inside the mouths of some jacks we have found huge, heavily armoured, fish lice two or three inches (5-10 centimetres) long. The presence of a couple of these creatures almost entirely bungs up the mouth of the fish.

Of course these are interesting facts. The gruesome life style of parasites holds a morbid fascination for us all, but does it matter to us as anglers? Why should we bother about the ways of lice with unpronounceable Latin names? Well, all species of fish are attacked by parasites; even the noble salmon and the mighty white shark are just as lousy as the rest. Parasites are certainly responsible for massive losses in fish production - probably on a par with the total commercial catch by all the gill nets, trawls and lines put together.

From another point of view, it is likely that a sickly or run down fish is most vulnerable to parasite attack. In other words a stressed fish is a fish at risk. Many things can cause stress, bad weather, lack of food, pollution, being chased by trawls, or even being scared by boats. We can gain some consolation from the fact that one of the least stressful of these pressures is being hooked, played and CAREFULLY released by anglers. Anyway, try to keep an eye open for parasites (and let me know – I’m an addict!), an increase in their numbers may be the first danger signs to indicate the impending decline of your favourite fish species.

If you have any comments or questions about fish, methods, tactics or 'what have you.'get in touch with me by sending an E-MAIL to - docladle@hotmail.com

INFORMATION SPOT

Fish parasites.

Copepods on ballan wrasse.

Sketch of Lernaeocera.