| If you want to see more archaeology click on the link. |  |

Information Page.

"In the beginning."

Over twenty years ago I wrote a piece about angling in the past. Since then my wife has become a full time professional archaeologist and I thought that it might be worth making use of one or two pictures and artefacts from her excavations on the shores of Poole Harbour, only a short walk from my house, to illustrate the words. Unfortunately there are no fish hooks or limpet scoops but no doubt the mesolithic hunter gatherers at Bestwall were cropping flounders, eels and salmon from the estuaries of the Rivers Frome and Piddle just as we do today.

| If you want to see more archaeology click on the link. |  |

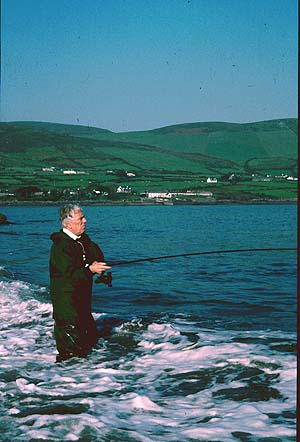

We take our modern fishing tackle for granted! Within minutes of arriving at the beach the very greenest novice can be casting his baited tackle 60 or 70 yards aided by a 10 or 12 ft ‘spring’ of carbon fibre.

His (or her) reel will be a miracle-of-modern-engineering, releasing line from an ultra-light spool, spinning at high speed on almost friction-free bearings or, retrieving, via a chain of gears, many times faster than is possible by hand and laying it, perfectly arranged on the spool.

The line, even if it is the cheapest monofilament, will be fine, transparent to the point of invisibility and strong, almost beyond belief. Wired grip-leads keep the tackle firmly in place on the sea-bed. Little coffins of synthetic polymer, keep the bait securely on the hook. The hooks themselves are barbed and plated alloy darts, smoothly curved, sharpened to points of molecular fineness and fantastically resilient. The whole set-up, in the right hands, is capable of securing the largest and most powerful fish which swims in our seas.

All-in-all we never had it so good but, hold on a minute! The allure and attraction of fishing obviously does not lie in the high technical developments of recent years. It may be possible to purchase a form of ‘instant success’ by buying expensive gear, chartering high powered boats with knowledgeable skippers or by travelling, at enormous expense, to far away virgin seas.

Whatever means we use to ensure our success, the satisfaction of angling, must at least in part, lie in making a good catch by our own guile and effort.

It was ever thus! From those first days when we dangled the innards of a limpet into a rock-pool to tempt the pop-eyed, aggressive blennies out of miniature caves and crevasses or lowered a decaying mackerel head from the quayside. We waited, with bated breath for the increased weight and tension on the line which meant it had gained a load of pinching clawing shore crabs.

We all know the combination of anticipation, skill, luck, suspense and satisfaction which is fishing. Since man first tried to supplement his food supply with creatures from another (watery) world, these feelings have appealed to those of us who have it in our nature to be fishermen or anglers. With all this in mind I have given some thought to the development of fishing skills. This relates not only to how we begin fishing when we are young but also to how sea fishing (in particular) was carried out in the years before the development of modern tackle.

No doubt then, as now, there were the good, the bad and the average exponents of angling. However, results must have depended to a much greater extent that at the present day, on the ability of fishermen to understand the vagaries of season, tide, wind and weather and to assess their effects on the presence and hunger of sea fish.

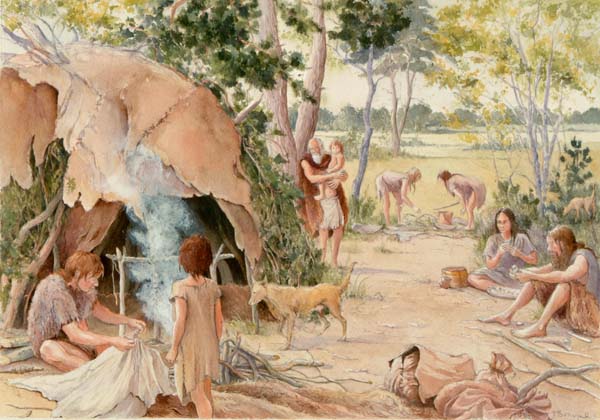

Just what sort of fish did people catch in pre-rod-and-reel days? First of all how can we find out? About seven thousand years ago stone age communities on the west coast of Scotland depended almost entirely on the sea for their living. Widespread evidence of their way of life is to be found on some Scottish islands such as Oransay.

Fortunately the waste disposal service in those days was not super efficient and consisted of what we might now call a rubbish tip or midden, handily placed outside the back door of the hut or cave. The main items remaining in these middens today are the shells of molluscs, particularly those of countless limpets which the mesolithic people are reputed to have eaten.

Broken tools and other rubbish also found their way on to these Stone Age rubbish heaps. A common implement is refereed to by archaeologists as a ‘limpet scope’. The scope is said to have been used for scraping limpets off rocks but it seems more likely to me that it was for removing the contents from the shells with out to much wear and tear on the thumb nail.

A little more recently (only 5000 to 6000 years ago) clay and stone boxes, set into the floors of houses are believed to have been used to keep bait alive. (Tell that to the wife the next time she complains about the dead ragworms in the salad drawer of the fridge).

In these northern waters the villagers used to fish for cod and coalfish, supposedly using limpets for bait. Apparently the Neolithic people were not stupid and ate the limpets only in times of severe deprivation.

Although the fishing lines have not been preserved, they were presumably hand lines of spun flax (which they used to grow). The hooks or gorge-pins must have been made from wood, bone or horn. It is impossible to know whether traps, nets, spears or lines were used to capture any particular species of fish and we can only speculate on the basis of what we know.

From the town of Hamwic, at the mouth of the River Itchen in Hampshire, there are detailed records of fish remains from about 1100 years ago. The most abundant remains were those of fish which would have been caught in the shallow waters of the estuary itself.

Flounders, eels, mullet, bass, salmon and even stingray would have been easily trapped, netted, or speared but the use of set-lines or hand lines, involving coarse fibres and crude hooks, was probably restricted to eels, flounders and bass. Gilthead sea bream, rare catches even today (although on the increase it seems), were also present in the remains.

It is more difficult to imagine how the Saxon fishermen caught the cod, thornbacks, whiting, mackerel, pollack and scad which were also found in Hamwic. Equally, it is curious thet there is no mention of conger, wrasse or other abundant or easily lured species, if conventional hook and line methods were in widespread use.

The absence of smoothhound and dogfish remains could be due to poor preservation of the cartilage of their skeletons rather than failure to capture them. Towns in the south eastern region of England, in mediaeval times, appear to have been dependant on cod, mackerel, whiting, and herrings to a large extent. A change in technology about 1000 years ago, possibly the introduction of the drift net, resulted in a hundred fold increase in the amount of herring remains in some excavations.

A complete list of species dug up from a site in Great Yarmouth by Wheeler and Jones was spurdog, thornback, eel, conger, garfish, herring, whiting, gurnard, turbot, flounder, plaice, halibut and sole quite a decent range.

The fish hooks taken in the same excavations were all big and crude and this is hardly surprising in view of the thick lines which must have been in use. Presumably only the larger and bolder biting species such as conger, spurdog, ling, cod, turbot and halibut were caught on hook and line. It is also recorded that eels and flounders were caught on hooks - neither are particularly fussy feeders. It is inferred, from the remains, that haddock and large cod may have been more common in the southern North Sea than they are at the present day.

All told, our ancestors managed to catch a great variety of sea fish, many of which would be desirable catches to modern anglers. Since their tackle was what we would describe as crude and their survival depended on what they were able to catch, it is likely that inshore fish were more abundant and that their knowledge of baits, times and places was extensive. One thing is for sure – the widespread problems of overfishing which we see today were not a thing of the past – catching fish was much too difficult.

If you have any comments or questions about fish, methods, tactics or 'what have you.'get in touch with me by sending an E-MAIL to - docladle@hotmail.com

INFORMATION SPOT

In the beginning.

Spinning for bass.

Mesolithic encampment.

Flint implements from the Bestwall excavation.

Salmon kelt.